Practical Advice for Riding the TransAmerica Trail

If you’ve ever wondered what really matters while riding the TransAmerica Trail — direction, timing, the right kind of stubbornness — there’s no better source for ground truth than Mark Pfefferle, a fellow Adventure Cycling tour leader who’s pedaled the route three times — and that doesn’t even include the time we both led a tour of the TransAm Express.

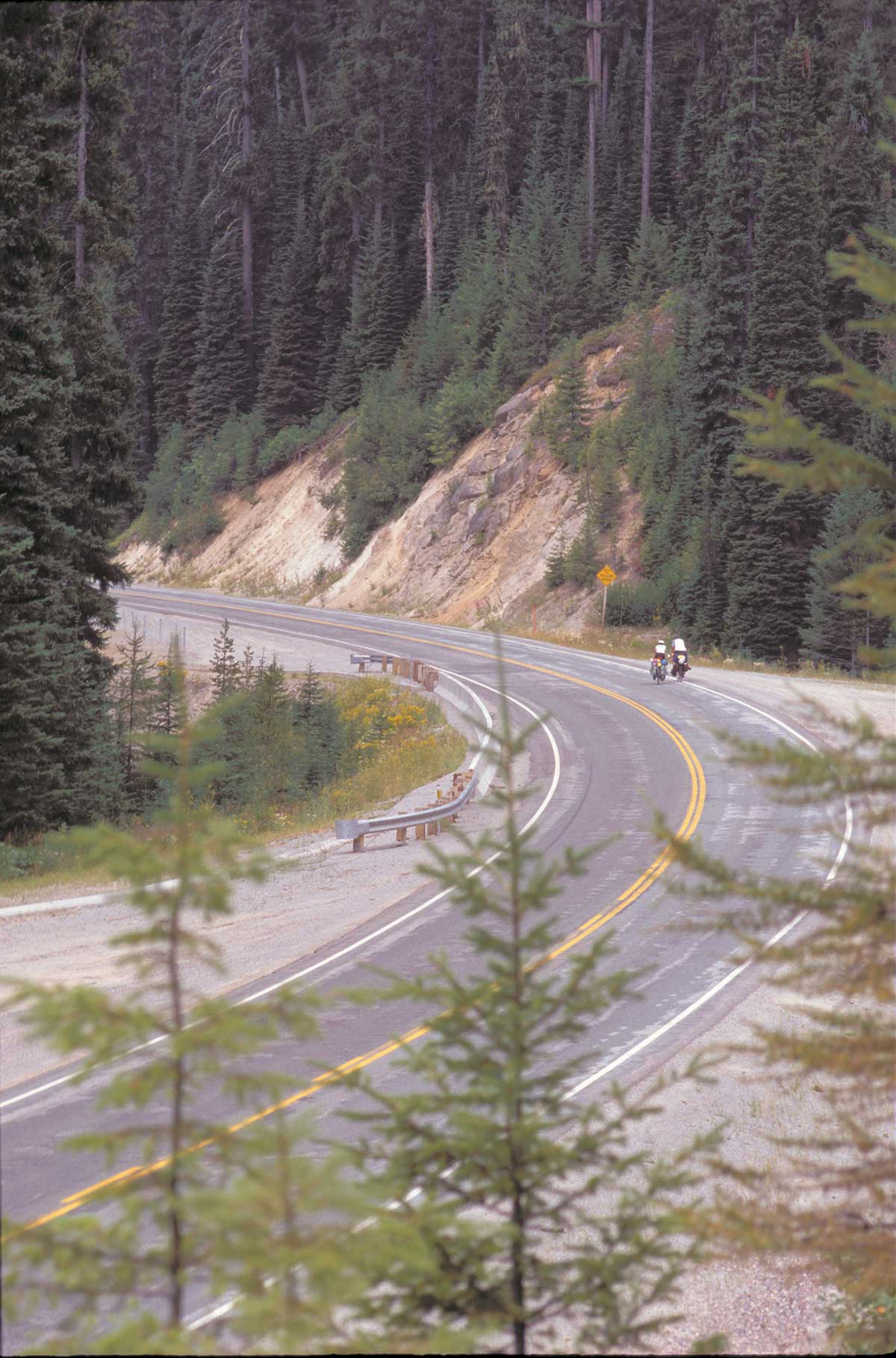

Ask him why he keeps coming back, and you’ll get a joke first, “Because I’m stupid!” The real answer is that there’s a familiarity and affection that beckons him. Virginia’s dense American history. The sandstone road cuts in Kentucky that line the shoulders like geology lessons. The way Kansas rises so gently that you don’t notice you’ve gained 2,000 feet until your legs tell you later. The Rockies that appear at first almost indistinguishably from clouds but soon fill the entire horizon.

Like many of us, Pfefferle navigates using Adventure Cycling maps, both paper and digital. The nonprofit has done the pathfinding so that we don’t have to, but despite the amazing amount of detail it’s managed to cram into its maps, over the course of 4200 miles, you’re bound to run into situations and decision points those maps can’t cover. So, consider this a friendly field guide from someone who is no stranger to this iconic ride.

Every Choice Has Its Pros and Cons

The first time Pfefferle rode the TransAmerica Trail, he rode it west to east. “I left Astoria on June 10 and rolled into Yorktown sometime in mid‑August,” he says. “Seventy days exactly.”

That first crossing, he was solo, self-contained, and didn’t see many riders. Maybe it was timing. Most folks heading west to east roll out earlier, but he’s not sure he would have made a different decision. “You have to get through the mountains. Start too early and you’d be stuck in snow or really cold weather.”

There was a downside to the late start, however, once he arrived in the Midwest: humidity. “It stayed that way to Yorktown. That’s draining; riding and sleeping in a tent on hot, humid nights where it doesn’t get below 70 degrees,” he says. “Not comfortable at all.”

The lesson wasn’t that he chose wrong. It was that every choice has its pros and cons. On the TransAm — or really any cross-country route — you can’t dodge discomfort completely; you pick what you think will work best for you.

Riding Solo vs Riding with Partners

Pfefferle didn’t wait long to make another crossing. In 2022 he rode east to west, and, crucially, not alone. He recruited partners through Adventure Cycling’s Companions Wanted service. Five riders started. “One quit after three days,” he says. “By Kansas, we’d split into pairs. Personality differences and different paces.”

He paired up with a rider named Sue, small in stature and a powerhouse on the bike. “She wasn’t afraid to ride in the dark, but she would not start early.” Pfefferle, on the other hand, would have preferred a prompt start to beat the wind and heat, and he remembers one particular day vividly. “We were on the bikes for eighteen or nineteen hours,” he says. “It was scary at times because of the cars coming up behind us in the dark.”

It’s just one visceral example of how riding partners can cure loneliness and provide support but replace them with logistics and compromise. Try your best to ensure your pace, priorities, and riding styles align before you set out, and then be willing to compromise once you do.

How Long Does It Take?

Pfefferle’s three crossings each took between 70 and 76 days. The faster trip included a handful of 100-mile sessions, but most days he averaged around 70 miles. His third crossing, done with his wife, Ann, averaged in the low 60s per day and included more rest days by design. “We could have finished four or five days earlier,” Pfefferle says, “but there was no reason to rush.”

Pfefferle’s also met several riders from Europe who were here on 90-day visas. “A lot of folks finish in seventy‑five or eighty days and then don’t know what to do for two weeks at the coast.” Those riders could continue down the Pacific Coast Route and take the train back from San Francisco.

Training that Actually Translates

If you only take one piece of advice from Pfefferle, let it be this: train with your bike fully loaded. Not just partially and definitely not empty. Your bike will feel like a different bike. Better to learn it three miles from home than three states.

So, put weight in your front panniers if you’re running them. Practice slow‑speed turns, starts, and stops and downhill braking. Then do a shakedown weekend where you eat what you intend to eat and sleep how you intend to sleep on the road. Verify your tent poles exist (don’t laugh; we’ve all had a friend). Bring your charging system and see if it survives the rain.

Eastbound vs Westbound

During Pfefferle’s third crossing, an opinion crystallized: east to west is easier. “Take McKenzie Pass,” he says. “West to east, you start in Belknap Springs at about 1,500 feet and go up to 5,300 feet, so close to 4,000 feet of elevation gain. East to west, you’re starting in Sisters, and you’re already at 3,000 feet. It’s more gradual.”

Still, there’s no direction that tricks the wind into obedience. You trade one pattern for another. “Going east to west, expect more headwinds in Wyoming and northern Colorado,” Pfefferle says.

Speaking of Winds … Know When to Wait Them Out

In 2024, Pfefferle and I led a TransAm Express together, and during our chat, we reminisced about the trip’s most memorable day. We had headwinds and sidewinds that literally blew us off the road. With a group of 14 and a schedule to keep, we pressed on. But if I’d been on my own self-contained tour, I would have hunkered down somewhere to wait it out. Pfefferle agreed. “There’s no reason to suffer like that,” he says.

On his most recent TransAm crossing with Ann, there was a day from Walden, Colorado, to Saratoga, Wyoming, when the winds simply said, “Stop.” The couple made it to Riverside, Wyoming, where they decided fighting forward just wasn’t worth it. There were reasons to get to Saratoga (a reservation at a favorite church hostel and a local hot spring), so they got a lift with an off-duty police officer. They have absolutely no regrets about the 20 miles they missed. Sometimes “Every Fun Inch” has some wiggle room when you’re crossing an entire continent.

Reservations and the 3 PM Decision Point

Pfefferle’s overnight strategy is simple because the best strategies are.

If he’s heading to a town with a single motel, he books the night before. If he’s taking a rest day, he books ahead so he isn’t looking for accommodations when what he really wants is to rest. Everything else is roll‑up. “Campgrounds are usually easy,” he says. “National Parks have hiker/biker sites, so you can just show up. If they’re full, other cyclists will usually make room.” RV parks, on the other hand, can be hit‑or‑miss on allowing tents. He checks their websites ahead of time, and if they don’t, there’s often another campground five or so miles down the road.

When he’s solo, Pfefferle waits until the afternoon to choose how far he’ll go. When you don’t have touring buddies or reservations, you have that freedom. “Three o’clock is when I start paying attention,” he says. “Twenty more miles or 40? I don’t worry about it until then, and it works out.” Once he had to ride thirty miles out of Missoula to find a campsite, and he only remembers that exception because it was so rare.

Can’t-Miss Towns

Some of these are places you’d never think to stop in on a road trip in a car. On a bike tour, however, your wants and needs change. Suddenly, a Warmshowers host who volunteers their washing machine and dryer is akin to a five-star hotel.

Oregon

It’s easy to linger in Sisters, where the air is fresh and pine‑scented, or in Mitchell, where the Spoke’n Hostel turns a night into a small reunion. “I’ve stayed there four times,” Pfefferle says. “At this point we’re friends. We hug when we see each other.”

Montana

West Yellowstone is touristy and exactly what you need for a layover day. You can ride your bike back into the park to visit the geysers or, even better, catch the shuttle.

Missouri

Farmington has Al’s Place, a cyclist hostel in a converted jail. It’s nice in and of itself, but it’s also within walking distance of downtown.

Kentucky

Berea announces the end of the Appalachians and, as Pfefferle likes to joke, the end of the dogs. (More on that later.) It’s also home to Berea College, a tuition‑free liberal‑arts school serving students from Appalachia — a mission the town takes pride in.

Virginia

Damascus is a fun spot to stop unless it’s during the Appalachian Trail Days Festival, in which case the town is one big party and maybe a little too much fun.

Trail Magic Goes Both Ways

On his second crossing, Pfefferle and his touring companion, Sue, were coasting into Houston, Missouri, when a man in overalls walked to his mailbox and, in the way of small towns, into their lives. “I could tell he wanted to talk,” Pfefferle says.

The man, Wes, invited them to stay out back. They hesitated; you couldn’t see the house from the road. But behind the tree line was a guest suite for cyclists with a shower, small kitchen, bed, and fridge stocked with beer donated by a local brewery.

Wes’s wife had died the year before. Before that, they’d hosted Warmshowers riders together. Pfefferle and Sue were the first riders to return. When Pfefferle and Ann came through in 2025, they stayed with Wes again. “I thanked him for hosting us,” Pfefferle says. “He said, ‘No, I want to thank you. You gave me the courage to do this again.’” Now Wes is listed in the ACA updates as a private host. Sometimes he even drives to the city park to collect weary riders who don’t know that they’re a friendly conversation away from a hot shower.

Touring Travails

If you haven’t ridden the TransAm, you might assume the hardest days are high and alpine. But Pfefferle disagrees. “The Ozarks,” he says. “They don’t believe in curves. They never thought of making a corner to go around those hills. The road goes straight up and straight down.” Humidity adds to the ordeal.

Wyoming offers its own kind of test with heat, long distances between services, and crosswinds that might try to blow you off the road. Start early, carry extra water, and know when to stop for a rest.

And finally, it’s not wild animals that are the biggest four-legged hazards. From Breaks, Virginia, to Berea, Kentucky, domestic dogs are part of the landscape. Pfefferle recommends attaching an air horn to your handlebar. “I’ve used it a few times,” he says. Once, Ann was about 15 feet in front of him when a hound came after her. “I hit the air horn, and the dog just stopped in its tracks. Then it was gone.”

Final Thoughts

When you set out, the enormity of cycling 4,200 miles feels like the point. Somewhere around Kansas, the point becomes the people who wave, the person at the coffee shop who cheerfully fills your water bottles (with ice!), and the stranger at a mailbox named Wes.

That’s the reason many of us keep coming back. It’s not because we forget about the fierce winds in Wyoming or dogs in Kentucky. It’s because we remember how it feels to pedal our way across this enormous expanse of country, each day brimming with potential, moments of joy, and small kindnesses waiting to be revealed.

Key Takeaways

- Train with the weight you plan to carry. Front panniers change handling; you want that learning curve to be close to home and as uneventful as possible.

- Start riding early in the day. It’s not about being hardcore; it’s about being done before the wind gets ideas.

- Be flexible and give yourself permission to stop. Snow in June happens. So do crosswinds that move you sideways.

- Don’t measure the worth of your crossing in pedaling every inch. Miss twenty miles in dangerous heat or a dust storm if that’s the safe choice. You still rode your bicycle across a continent.

- And, truly, bring the air horn. You’ll thank Pfefferle when a dog is charging straight at you and changes its mind five feet from your ankle.