Bikecentennial: Summer of 1976

Think of an event, any event. Make it something close to your heart-something bordering on an obsession. Don’t concern yourself with staying within the bounds of feasibility or practicality. Now imagine 40 wildly enthusiastic people rushing to your side, first in a trickle and then in a flood, with their sole purpose being to make your implausible event happen. Your event does happen; not exactly as you first dreamed of it, not on the scale that you imagined, but it does happen.

Afterward, instead of fading back into the recesses of your mind like a mist disappearing in the shadows, your event hangs on, transforming itself into an organization that, ultimately, employs you and inspires nearly 50,000 other people to join you in support of the idea behind your dream.

That, in a version that even Reader’s Digest would find condensed, is how Bikecentennial, Adventure Cycling’s predecessor, came to be.

I pictured thousands of people, a sea of people with their bikes and packs all ready to go, and there would be old men and people with balloon-tire bikes and Frenchmen who flew over just for this. Nobody would shoot a gun off or anything. At 9 o’clock everybody would just start moving. It would be like this crowd of locusts crossing America.

Greg Siple, Adventure Cycling’s art director and co-founder, thought of his implausible event in December 1972, while riding the California Coast. In San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, he found a starting point: "My original thought was to send out ads and flyers saying, ‘Show up at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco at 9 o’clock on June 1 with your bicycle. And then we were going to bicycle across the country. I pictured thousands of people, a sea of people with their bikes and packs all ready to go, and there would be old men and people with balloon-tire bikes and Frenchmen who flew over just for this. Nobody would shoot a gun off or anything. At 9 o’clock everybody would just start moving. It would be like this crowd of locusts crossing America."

To understand Greg’s astonishing train of thought, you have to place him in context (not an easy task). He was in San Francisco not by chance, but as a participant in an 18,000-mile bicycle ride, called Hemistour, traveling from Anchorage, Alaska, to the tip of South America, Tierra del Fuego. The first people to enthusiastically embrace the idea of the mass ride were Greg’s wife June, and the other Hemistour couple, Dan and Lys Burden.

In San Francisco, Hemistour was riding a wave of success. One of the goals of the ride was to bring publicity to the sport of bicycling. Initially contacted by letter, National Geographic magazine had taken an interest in Hemistour, and was providing film and traveling money. The magazine’s original agreement was to provide 60 rolls of film. But, when the first photos came back, they were impressed enough to fly Greg and Dan to Washington, D.C., for a heady, whirlwind tour of the offices and an inspiring glimpse of the mammoth organization’s resources, including legions of editors, writers and photographers.

In April 1973, while in Mexico, still shooting hundreds of Hemistour photos for National Geographic, the four began to talk about the bicentennial ride as if it could happen. In Chocolate, Mexico, they decided it would happen. June gave the event a name: Bikecentennial.

When they reached Mexico City, Dan and Greg decided to create a flyer to announce Bikecentennial to their friends and to seek support. Those friends included most of the people involved with cycling on a national level at the time – not a great many people then, or even now, but they were people who could make things happen in bicycling. Many of these contacts had come from Greg and Dan’s years of involvement with the Tour of the Scioto River Valley (TOSRV) in Ohio.

"I went into a small office supply shop, borrowed a typewriter, and composed the original copy," Dan recalled. "It seemed we should have a route to describe. The logical choice was to stay well to the north of the vast deserts."

Meanwhile, Greg prepared the graphics for the flyer, entitled "Two Wheels, Two Centuries." More than 100 flyers were mailed that week. It was June 1973.

A month earlier, National Geographic had run an article about the first leg of Hemistour, from Anchorage, Alaska, to Missoula, Montana. After reaching Oaxaca, Mexico, about 200 miles south of Mexico City, Dan, Greg and Lys flew back to Washington, D.C., to discuss a second article with their editors at the magazine. The trip was also a chance to determine what sort of interest, or lack of interest, the flyers had stirred up. Frustrated with the group’s inability to communicate in Spanish, June opted to attend a language school in Guatemala.

The return to the United States brought both success and failure. For National Geographic, the thrill of Hemistour was gone.

Although the official withdrawal of their support would come later via mail, Greg sensed on this second visit that a letdown was in store. However, as the prospects of Hemistour continuing to appear in one of the nation’s largest magazines wilted, the outlook for Bikecentennial brightened considerably.

The initial mailing of 10,000 flyers went to bike clubs, bike shops, and other pockets of cyclists throughout the United States and overseas.

To their surprise, the trio learned the idea as outlined in the Mexico City flyer was already circulating in some bicycling publications. Also, Noel Grove, a writer at National Geographic, had become an enthusiastic supporter of the Bikecentennial concept. He introduced the Hemistour participants to his boss, assistant editor Carolyn Patterson, who, aside from her work at National Geographic, was involved with an organization called Open House USA.

Open House USA managed lodging for foreign professionals visiting the United States and for American professionals visiting foreign countries. If you were a Belgian doctor with a hankering to see the Big Apple, for example, Open House USA would find a New York City doctor for you to stay with during your visit. Patterson was intrigued by the Bikecentennial idea because she saw it as a way to bring more foreigners to the country, who would need more open houses. At a luncheon discussion, she offered to write a check for $1000 to help get Bikecentennial started.

"We were a little bit suspicious (of her offer)," Greg said, "but the only requirement was that any published materials include a credit line for Open House USA. So I went to Schenectady to stay with my parents and turned out stationery and flyers."

Dan and Lys returned to Columbus, Ohio, to stay with Dan’s parents and work on what they thought would be a second National Geographic article. Staying in touch by mail, Dan and Greg put together the copy and graphics for their new flyer: "Bikecentennial ’76. The 76-Day, 3,000-Mile Bicycle Birthday Party." (The actual TransAmerica Bicycle Trail mileage was closer to 4,250 miles.) Later, in the form of a magazine ad, this flyer design would become one of Bikecentennial’s most effective producers of inquiries. The initial mailing of 10,000 flyers went to bike clubs, bike shops, and other pockets of cyclists throughout the United States and overseas.

Meanwhile, Dan received a letter from Robert Loewer, Corporate Relations Manager of Huffman Manufacturing (Huffy Bicycles) saying, "Count us in, we’ll do a poster." Loewer was a friend, one of the many contacts the pair had made through pitching Hemistour to the industry and their work with TOSRV. On behalf of Huffman, Loewer committed to $1,500 for a 5-color poster announcing Bikecentennial – a product Dan saw as vital.

"The poster allowed us to (explain) the Bikecentennial concept to several thousand people we knew were writing in," he said.

At this point, things began to get complicated. Dan had been suffering from a severe cold on leaving Mexico. His appearance had deteriorated steadily since. He was 20 pounds underweight, gaunt and anemic. Sixteen days after his return to the United States, Dan checked into a Columbus hospital with an acute case of hepatitis. For he and Lys, Hemistour was over.

Greg and June, however, were determined to complete Hemistour. They decided to continue on without their friends. For them, it was Bikecentennial that was over, at least for the next two years. Their only contact with the project would be through the mail.

On his way to Texas to meet June and continue into Mexico and South America, Greg stopped in Columbus and introduced Dan to Lynn Kessler, a friend from art school and a recent convert to cycling. After a meeting in which he showed his portfolio, Lynn agreed to pick up the graphic gauntlet for Bikecentennial during Greg’s impending absence.

During the next two years, Lynn designed Bikecentennial’s ’76 logo, its stationery, fund-raising packages, membership materials, newsletters, promotional literature, and a poster-all on a volunteer basis.

"Lynn made the Bikecentennial idea look good in the mail," said Greg. "Without Lynn or some other artist filling this role, Bikecentennial would have been without one of its greatest assets – quality promotional materials."

Despite the strong graphics, however, the Bikecentennial idea was still ill-defined. In late August and early September, Dan set about to correct that problem. He turned again to the friends he and Greg had made during their TOSRV days, including Charlie Pace, TOSRV’s long-time director, and Scott Warner. Charlie stressed the fact that it was not too early to begin planning and pointed out the importance of making community contacts along the route, once the route existed.

Scott Warner laid the mass ride concept to rest in favor of providing facilities along the way and sending cyclists across in small groups throughout the summer. Before anything could happen, though, there had to be the route. At that time, only one section of what was to become the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail was determined – it would follow the Hemistour route through Oregon and Idaho. The remainder of the route consisted of a vague notion; something well north of the deserts of the Great Basin, but not too far north. The design of the trail fell to Lys Burden, as Dan’s hepatitis was hanging on.

Lys had found an extraordinarily well-paying job in a Columbus beer factory. In one month she earned $1300, enough to finance her initial research of the trail, which she began in November of 1973, traveling from the Williamsburg area to Missoula. She was determined to stick with the research for as long as it took, which turned out to be quite a while.

"Lys Burden was the architect of the Trans America Bicycle Trail," said Stuart Crook, Adventure Cycling’s former Leadership Director. "When I joined Bikecentennial in the summer of 1975, she had been working on it, designing it, for two years."

Toward the middle of December 1973, Dan’s hepatitis had cleared enough to allow him to organize a mass mailing to those who had requested additional information about Bikecentennial. The mailing to 3,000 people took two nights of work by a group of friends and family in Columbus. As an afterthought, they decided to throw in a 5 x 7 flyer asking for $10 to be placed on a permanent mailing list and to help fund the program. The forerunner of today’s membership, this simple idea eventually brought in more than half of the monies required to launch Bikecentennial, according to Dan.

Two days after this mailing, Dan flew to Missoula, where he had attended the University of Montana, to re-establish a home.

"It was a logical place to start Bikecentennial, since I had many friends, a university from which to draw talent, and a place where we could live inexpensively, attending school on the G.I Bill during the day, working on Bikecentennial at night," Dan said.

By late December 1973, Dan and Lys had leased a small, one-bedroom apartment in Missoula for $85 per month. For the next year, the apartment would serve as Bikecentennial’s modest headquarters, as well as Lys and Dan’s home. During that year, Dan would embark on a series of fundraising efforts that never quite produced the big dollars, though there were small successes.

Aside from his fundraising efforts, Dan began laying the structural groundwork for Bikecentennial. A friend at the University, Mike Gauthier, volunteered to set up a basic accounting system for Bikecentennial. Mike also talked his accounting professor into having the class research the possibility of the organization assuming a nonprofit status. As a result, Dan was shown how Bikecentennial could qualify for a nonprofit status, which later would bring special postage rates and the ability to accept charitable contributions.

Through other friends and advisers at the university, Dan explored the possibility of incorporating the organization. After several meetings in February 1974, one of the professors involved suggested a lawyer who would volunteer to help Dan through the incorporation process. On March 15, 1974, Bikecentennial became Bikecentennial ’76, Inc.

Meanwhile, Dan was gathering together a group of people he called "the silent decision makers." The forerunner of today’s Board of Directors, this group consisted of "well-respected bicyclists, agency officials and members of the biking industry." Dan built up many of these contacts through correspondence or inherited them from Lys, who had sold the Bikecentennial idea to state and federal officials during her route research.

Dan looked to the loosely knit group for advice on the trail, the program, and the organization. In the spring of 1974, he made two trips to the east for meetings with some of his silent decision makers. Bill Wilkinson, then with the Department of Transportation and now the Deputy Director of the Bicycle Federation of America, was invaluable to Dan on his visits to Washington D.C. Bill knew his way around the corridors of government and was able to arrange many meetings with officials in the labyrinth of agencies that flourish and grow in the nation’s capitol. Nothing immediate came of these meetings, but Dan felt he was able to lay the groundwork for future success within the agencies.

One of Dan’s trips to the east was a follow-up to an earlier visit with Huffy. Fred Smith, Chairman of the Board for Huffman, had agreed to go before the Bicycle Institute of America (BIA) and seek direct support of up to $100,000 for Bikecentennial. The BIA had already donated $2,000 to assist in Lys’s trail research. Now they donated an additional $5,000. The $100,000 grant was never to be.

It was time for test pilots – people on bicycles to ride across America on the route that Lys had created while traveling in a Volkswagen bus. In late 1973, Jim and Es Kehew, an active middle-aged couple from Pennsylvania, had written to Greg, offering to help by riding the trail in the summer of 1974. Now, with the $5,000 in BIA money in hand, Dan contacted the Kehews and told them they were on for the summer.

Dan also heard from Jim Richardson and Linda Thorpe, a young California couple who had read about Bikecentennial in Bike World magazine. Jim and Linda announced that they were going to ride across the country on a tandem, courtesy of a sponsorship from Weight Watchers. They wondered, did Bikecentennial have any suggestions for a route? Suddenly, Dan and Lys had two route-testing teams.

The Kehews had smooth sailing across the country, with not so much as a flat tire. Jim and Linda got more flat tires, 120 more to be exact, and more press. Their ride was covered in three wire service releases and received widespread publication in newspapers across the country.

After the summer ended, Dan convinced Jim to return to Bikecentennial rather than to law school. Jim and Linda became Bikecentennial’s first field team, without a salary, but with their travel expenses paid. As a field team, they began the tedious process of making contacts in the communities along the trail, arranging for overnight facilities, sources of food and any other support they could convince local residents to provide. Eventually, the pair would become Bikecentennial’s National Field Directors and would play central roles in the organization.

When Dan returned to Missoula after one trip east in May 1975, Lys gave him the news of Bikecentennial’s biggest financial score: a $26,700 grant from the American Revolution Bicentennial Board.

"At last, we could hire staff, fund final research, and hold to our promise that there would be a trail," Dan said.

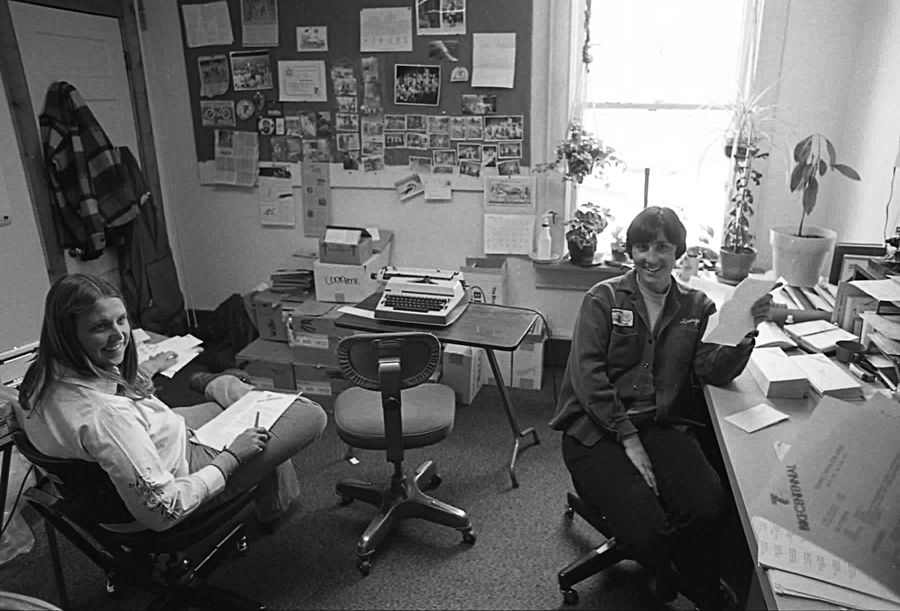

Earlier, in December, Bikecentennial had moved into offices in the former Belmont Hotel, above Eddy’s Club on North Higgins Street. The rent was reasonable, the walls were do-it-yourself. Within eight months, by August 1975, the original three offices would grow to more than 30, covering the second floor of the building and pushing up into the third floor.

An important link with the bicycling industry was established when Shimano became interested in Bikecentennial, sending two people to visit "world headquarters" in Missoula. One of those sent, Matthew Cohn, later became Bikecentennial’s publications director, and still serves on Adventure Cycling’s Board of Directors. Shimano liked what they saw well enough to donate 1,000 caps, 1,000 shirts, 2,000 water bottles and 5,000 posters to sell. But, more important, Shimano legitimized Bikecentennial in many people’s minds by mentioning the event in their advertisements. Bikecentennial was now backed by a major corporation.

The summer of 1975 was a fascinating, intense period in Bikecentennial’s development. In those three months, the handful of people already involved saw the staff grow to 40 full-time employees. Even those who initially were only mildly interested quickly worked themselves into the frenzy that predicated 14-hour workdays, seven days a week, for months on end leading up to the big event.

For many, Dan was the magnet that bound them to the work. They came to the organization in a variety of ways and for a variety of reasons, but once they got there, they eventually encountered Dan’s infectious and effective hyperbole.

"When Dan talked about (Bikecentennial), it was like the whole country was going to ride across. Everyone was going to be there, we were going to take up all the roads, we were just going to take over the world," remembered Charlotte Henson.

Charlotte was a long-time acquaintance of Dan’s, going back to the circle of friends which included Dan, Lys, June and Greg, all involved in the American Youth Hostel (AYH) Columbus Council in Columbus, Ohio, now known as Columbus Outdoor Pursuits. After graduating from college in 1975, she came to Bikecentennial on the bus, with everything she owned stuffed in a backpack. She began by doing simple chores around the office and making lunches. She was then put in charge of finding 12 trailhead coordinators, who would handle the food, money, and accommodations for cyclists beginning at various locations, or "trailheads," along the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail. Charlotte quickly realized that she was not qualified for the job.

"I didn’t know anything about hiring anybody," she recalls. "I put ads out in bicycling magazines. People wrote in and I had no idea how to pick them out. The salary was next to nothing. But overall, the people I got were good people."

First, most of the staff came with a fair idea of what they wanted to do and then found out what they actually would be doing. Job descriptions were formulated using something akin to the stream of consciousness technique. Second, very few were trained for what they eventually would be doing. Third, no one made more than enough money to live on. Fourth, everyone was idealistic. Fifth, everyone got the job done through hard work, and on-the-job training.

If Bikecentennial wasn’t fulfilling Charlotte’s lifelong career goals, neither was it fattening her bank account.

"We all had about the same salary ($250 to start, $300 a month tops), and everyone took kind of a pride in living simply. Bicycling to me somehow symbolized clean, moral living. I was really caught up in the whole thing. I was never going to own a car," she said.

Charlotte’s experience as a staff member of Bikecentennial is characteristic in many ways of the experience of every staff member during that period from the fall of ’75 to the summer of ’76.

First, most of the staff came with a fair idea of what they wanted to do and then found out what they actually would be doing. Job descriptions were formulated using something akin to the stream of consciousness technique. Second, very few were trained for what they eventually would be doing. Third, no one made more than enough money to live on. Fourth, everyone was idealistic. Fifth, everyone got the job done through hard work, and on-the-job training.

"There was always this feeling that there was no sheet to tell us how to do this," said Gary MacFadden, now Adventure Cycling’s executive director. "We felt that we were working on something totally new, something that had never been done before. We were right."

In June 1974, Gary had just graduated from the journalism school at the University of Montana. He saw a handwritten 3 x 5 card on the school’s bulletin board: "Cycling group needs editing of guidebook materials. He called for an interview, got his first look at the organization’s offices above Eddy’s Bar, and went home, unimpressed, but harboring a kernel of interest. One month later, Gary received a call from John Briggs, Bikecentennial’s volunteer slide show producer and part-time college student.

John offered him the editing job. What Gary expected to do was to create the set of five guidebooks for the TransAmerica Trail maps using material sent in by regional editors. What he got was a gasoline credit card and a Coachman motorhome that would sleep seven, had a shower, bathroom, refrigerator, and two air conditioners. (Coachman Industries, after seeing John’s Bikecentennial slide show, had agreed to loan the organization a motor home for summer research trips.)

Before long, Gary would be sliding the giant rig (dubbed the "Ameripig" by pristine, non-car-owning staff members) in sheer terror down rock-strewn Appalachian backroads designed more for mules than motorhomes.

During the 2 1/2 months he spent on the TransAmerica Trail in the motorhome, Gary gathered two kinds of material: natural history and local history. He wanted the guidebooks to include facts and anecdotes that never make it onto federally funded highway markers, and so interviewed locals extensively. He discovered that the TransAmerica Trail ran through an America that was rich in small-town history.

When Gary returned to Missoula late in the summer of 1975, he found about 20 staff members he had never met and an almost equal number of offices that had not previously existed. This was indicative of the meteoric growth of the organization during this period. Gary carried with him boxes of notes for the production of the guidebooks, but he was unable to get started right away. There were other projects to be done, such as a redesign of the organization’s newsletter, the BikeReport (predecessor of the Adventure Cyclist you’re holding in your hands now).

Gary remembers adopting a typical Bikecentennial work schedule. "People who recall me at that time remember me staying in one office toward the front of the building with the door locked. I’d drink coffee from 9 to noon, Coke from noon to about 7, and coffee until I went home around 1 a.m."

Bonnie Hoffman and Tim Liefer came to Bikecentennial in the summer of 1975 to help with the organization’s first two leadership training courses. Bonnie had been an American Youth Hostels (AYH) trip leader for seven years and served regularly as an adviser in their leadership training program. She and Tim had met at an AYH course.

In the summer of 1974, Bonnie visited Tim at college in Madison, Wisconsin, and he told her about an organization he’d read about in Mother Earth News. The organization was Bikecentennial. "We should really do this," he said. "It’s right up our line."

After corresponding with Dan, they agreed to design and run Bikecentennial’s first leadership training course but made it clear that they didn’t want to be involved in the leadership program. They wanted to be a field team. Of course, they ended up running Bikecentennial’s leadership program, training almost 600 leaders in a year, half of whom actually led trips. Bonnie had the contacts to staff the Bikecentennial training courses because she knew so many of the AYH leaders and advisers from her years of involvement with that organization.

"Every time I picture myself at Bikecentennial, I’m sitting up in that office at my typewriter, writing letters," she said. "It was a big job to get a director and four advisers for every course. I had to find enough people with the time and knowledge to do it. Most of them were personal friends. I wasn’t writing to anyone I didn’t know or hadn’t worked with at AYH."

Tim took care of the leadership program’s accounting and logistics by determining the costs, keeping it solvent, getting supplies to course locations, finding course locations and screening the leadership applications. At one point, well after she and Tim had caught the Bikecentennial fever and were in no danger of recovering from it, Bonnie mentioned to Dan that she figured he never intended for them to be a field team. His reply: How would they ever have gotten enough leaders without her contacts?

Stuart Crook was one of those leaders trained at the courses in the summer of 1975. He wanted to lead a TransAmerica trip. Instead, he worked as a regional coordinator, responsible, with his wife Polly, for the 800-mile section of the trail from Berea, Kentucky, east to Yorktown, Virginia.

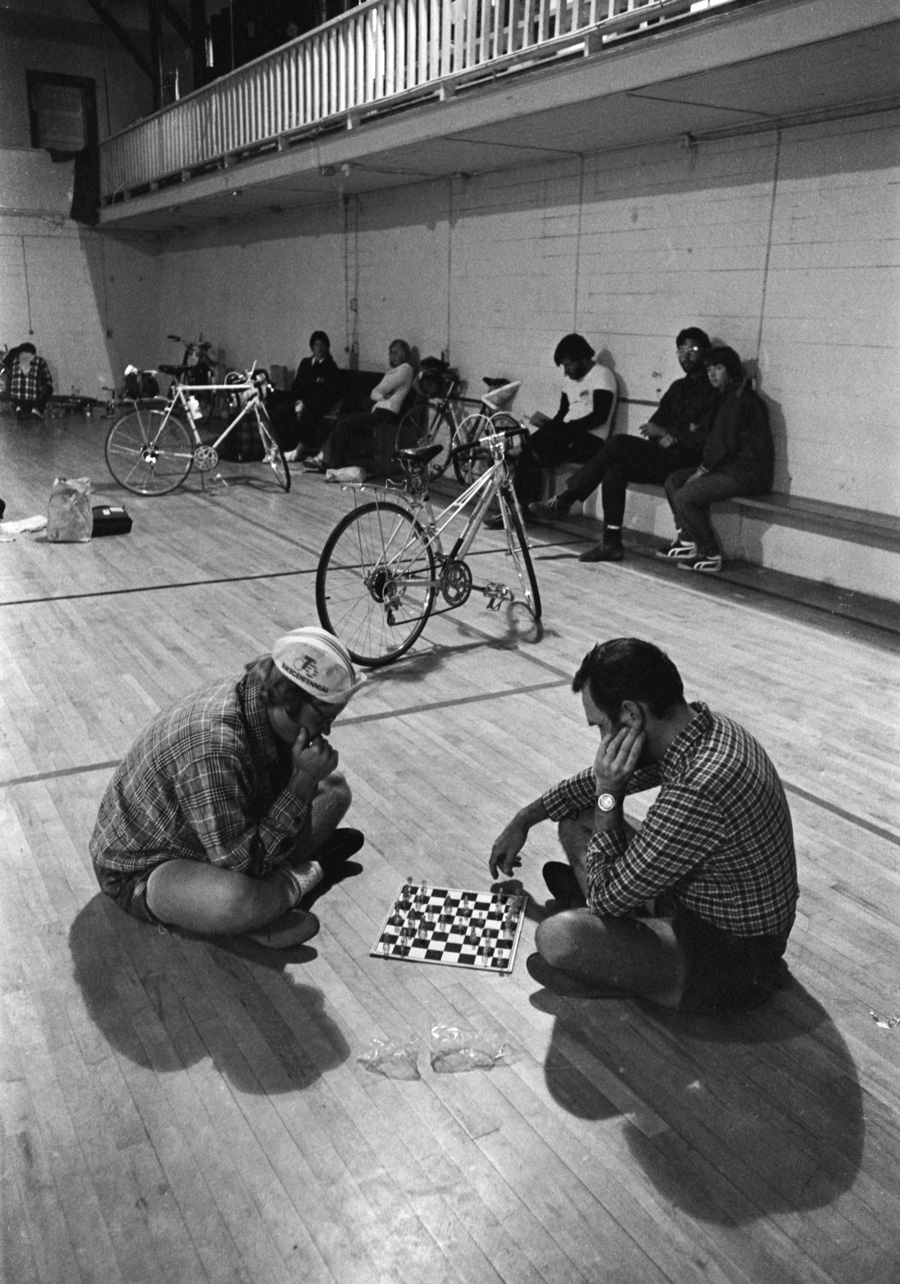

Stuart and Polly arrived in Berea early in May of 1976 to find that many of the Bike Inns were not set up. Bike Inns were temporary indoor overnight stops for the TransAmerica cyclists, who would begin hitting the trail toward the end of the month. So Stuart and Polly spent the month going to small churches, schools, gymnasiums, VFW and Foreign Legion halls, and anything else with at least a partial roof in rural Appalachia, saying to those in charge, "There’s gonna be 10,000 people coming through here on bicycles this summer, can they stay in your building?"

Stuart remembers most of the reactions as not disbelief, but incomprehension.

"To many of the locals, the idea of an adult as opposed to a hippie, riding a bicycle across the country was about as comprehensible as they themselves flying to the moon," he said.

Through lots of talking, Stuart and Polly were able to establish the personal trust needed to convince the local people that this event could happen and that it would be all right if these adult cyclists stayed in their towns. It didn’t hurt to be married, either. A farmer in Virginia agreed to have his pasture converted to a temporary campground only after establishing that Stuart and Polly had been joined in holy matrimony. In the end, the pair established all the Bike Inns they needed well before cyclists began arriving.

Back from Tierra del Fuego, Greg and June Siple eventually found their way to Missoula – June arriving in the summer of ’75 and Greg in the fall of ’75. Greg came later because he decided to let the momentum of Hemistour carry him to Europe, where he led a trip for AYH.

True to Bikecentennial form, June’s job wasn’t quite what she expected. She had intended to organize a program for disadvantaged youth to ride the TransAmerica Trail, but instead was given, among other duties, the responsibilities of the Sales Department and a campaign to draw foreign riders to the event.

Greg, in one of the truly remarkable moments in Bikecentennial’s history, came to Missoula to do exactly what he expected to do and what he was trained to do — to work as a graphic artist. He’s still doing it today.

The 12- and 14-hour workdays, combined with little or no time off in the months leading up to the event, would leave some of the Bikecentennial staff too dazed to fully appreciate what they had accomplished when it happened that summer. The transformation of the staff into something resembling a family, working together nearly 24 hours daily strained some personal relationships to the breaking point.

"Somebody should have been kicking us out of the office at least one day a week," reflected June.

And, money continued to be a significant problem throughout the period leading up to the summer of ’76. Bankruptcy was always a possibility.

"It was like a group in a lifeboat," said June. "We were having a great time but we were worried about the sharks. We were bailing and singing camp songs at the same time."

Despite their problems, familial and otherwise, the Bikecentennial staff retained a sense of purpose and excitement. Because on the horizon loomed a cloud of heavy summer dust, stirred up by thousands of pairs of wheels, as cyclists from around America and the world gathered to celebrate a 4,250-mile bicycle birthday party.

Other than Bikecentennial, no major bicentennial event that we know of gave celebrants the opportunity to actually do something. Bear in mind too, that most of the TransAm riders were strangers to each other, thrown together for the biggest challenge of their lives. Ten percent of the 4000 riders who took part in the celebration were from overseas (200 were from Holland alone) where they were accustomed to hostels with fully stocked kitchens, bunk beds, and other amenities. But the majority of Bikecentennial riders, Europeans included, ignored the minor inconveniences. They didn’t dwell on the lack of a kitchen (and bunks) at last night’s Moose Lodge. Strangers became friends. They kept their eyes on the big picture — riding across America.

The December 1976 issue of BikeReport ran a short article called "The Numbers" in which it was reported that "In 1976, Bikecentennial operated 300 trips servicing 4,100 men and women. All fifty states and several foreign nations were represented. Just over 2,000 bicyclists rode the entire length of the trail."

They’re impressive numbers. Unprecedented numbers. But they hardly tell the real story of the Summer of ’76. Many cyclists who took part in 1976 (and those who take TransAmerica trips today) say essentially the same thing about the experience: "I learned more about this country in 90 days than most people learn in a lifetime."

And more about themselves. Every one of us should, someday, have an experience like the Bikecentennial summer of 1976.

Dan D’Ambrosio wrote this article on the history of Adventure Cycling for the organization’s 20th Anniversary in 1996. You can also download D’Ambrosio’s 2006 Adventure Cyclist article (PDF) on the history of Adventure Cycling.