Woodrow Wilson, Cyclist

If Donald Trump is to go down as one of our nation’s most, shall we say, controversial presidents, he will have to beat out Woodrow Wilson, his predecessor from a century ago. And that will be no easy task.

Though twice elected to the nation’s highest office, the Southern-born Democrat left behind a checkered record at best. The centennial of our entry into World War I this year is bound to rekindle the acrid debate about whether Wilson should have stuck to his reelection campaign promise to stay clear of that notorious bloodbath. And by failing to establish an effective League of Nations in its aftermath, he arguably bungled an opportunity to secure a more peaceful world. Then he served out his last two years mentally incapacitated by a stroke. Even his reputation as a social progressive who supported women’s suffrage has come under fire — just last year, a group at Princeton, Wilson’s alma mater, persuaded the university to remove a wall-sized photo of the former president, branding him a racist.

Yet whatever history may make of Wilson, he had at least one redeeming quality: he was an avid cyclist. In fact, he was the first cyclist ever to occupy the White House and quite possibly the one who most treasured the bicycle.

After all, he was practically an eyewitness to its inception. In all probability, on March 1, 1869, 12-year-old Woodrow of Augusta, Georgia, watched the Hanlon brothers ride up and down Broad Street on their newfangled velocipedes. He may even have ridden the old boneshaker himself because two rinks flourished briefly near his home (now a house museum).

But his true introduction to cycling came in the early 1880s when his little brother Joseph took up the sport of high wheeling. Like many privileged young American men his age, Josie, as he was affectionately called, was captivated by the majestic “English Bicycle,” the second-generation machine that had been developed in Europe in the 1870s.

To join the elite fraternity of wheelmen, one needed a bicycle (costing about $100, a princely sum at the time), some athletic ability, and a willingness to take an occasional tumble. In return, a rider gained the ability to swap the gritty city for the serene outdoors, savoring nature as no noncyclist could. This healthful lifestyle involved moonlit rides and military-style parades as well as ample downtime spent at lavish club banquets or simply lounging at the posh clubhouse.

In 1883, at the age of 16, Josie bought his first bicycle, a 52-inch–diameter Columbia. By this time, the Wilson family had relocated to Wilmington, North Carolina, sans Woodrow who, 10 years older than Josie, was already on his own and practicing law in Atlanta. Josie and a friend promptly founded one of the first bicycle clubs in the South, commandeering the Wilsons’ basement to serve as its headquarters.

Josie told Woodrow about these exciting developments, closing his letter with “Hurrah!!!! For the bicycle.” From then on, Woodrow received regular reports from Josie extolling the virtues of bicycle riding while decrying the growing backlash against cyclists from carriage drivers, who charged that the “silent steed” scared their horses. Josie did his part for the cause, suing the state of North Carolina to give wheelmen access to a local turnpike.

Unlike Josie, however, Woodrow did not truly fit the wheelman mold. For starters, he was not much of an athlete. At five feet 11 inches, he towered over his younger brother, and he had played some baseball in his college days, but both his eyesight and his general constitution were poor. Besides, he was approaching the 30-year milestone, an age when many wheelmen hung up their wheels to get on with life. Indeed, Woodrow was already dating the woman he would soon marry, Ellen Louise Axson.

Josie nevertheless pleaded with his older brother to give the Columbia a whirl. “My bicycle tells me to tell you,” prodded Josie shortly after purchasing his mount, “that it is waiting anxiously for you to mount it next summer as you said you would.” Woodrow did gain custody of that bicycle in the summer of 1884 when Josie went off to military school. That fall Josie grilled his brother: “Did you ride my bicycle at all after I left?”

Whether Woodrow ever dared to mount the Columbia and take it on a furtive spin or two is not known; his letters to Josie are lost. Even if he did, he never succumbed to high wheel fever. And, by 1887, it seemed that Woodrow would never cycle. He had married Ellen, become a father to the first of their three daughters, and was fully engaged in his new career as a university professor, teaching ancient history and international law.

Josie, meanwhile, became ever more immersed in the high wheel culture. In 1885, after the family moved once again, to Clarksville, Tennessee, Josie became the secretary-treasurer of the local bicycle club, as well as an agent for the Columbia and Rudge bicycle brands. “The wheel not only affords much pleasure to those who can control it,” ran one of his ads in a local newspaper, “but [it is also] very useful.”

At the same time, Josie enrolled in Southwestern Presbyterian University, where his father taught theology. But Josie made no secret of his priorities. “The time will come, when there will be a professorship of cycling in the larger colleges,” he needled Woodrow, who was then teaching at Bryn Mawr. “So when you get a chair at Princeton you can ‘get me in’ [there] as an instructor of cycling!”

But to the family patriarch, Joseph Ruggles Wilson, Josie’s obsession with cycling was no laughing matter. “Josie studies a little and goes out a great deal,” he vented to Woodrow, adding, “I have grave apprehension as to his future.”

Woodrow, for his part, seems to have tolerated, if not outright encouraged, his brother’s dalliance. As a gift for Christmas 1888, he sent Josie a subscription to Outing (the magazine that had sent Thomas Stevens “around the world” on his Columbia high wheeler.) Josie gushed: “You could not have pleased me better, for I am more of an enthusiast on the subject of wheeling than ever.”

The previous summer, Woodrow had even welcomed Josie and his bicycle to the Wilson home in Bryn Mawr. And although the older brother continued to resist riding the bicycle, he knew that he desperately needed to find some sort of healthy physical outlet. His busy life was bringing him constant headaches and long bouts of fatigue.

Stockton Axson, who was also a guest at his brother-in-law’s home that summer, recalled in his memoir the stark physical contrast between the two brothers. The one who “rode with enthusiasm the old-style high-bicycle, dressed in a natty suit of blue,” was the very picture of youth and vigor. The other virtually embodied middle-aged malaise.

Stockton knew well that his low-keyed brother-in-law would never emulate Josie or his fellow wheelmen perched on their high bicycles, for to him they were merely examples of “boys doing what men disdained.” Still, Stockton noted at the time, perhaps cycling was not entirely out of the question for Woodrow after all. “Among the numerous high wheels ridden by young men,” Stockton recalled, was an occasional “odd looking low-bicycle called a ‘safety.’”

Although it was at first widely dismissed as an eccentricity, the diminutive chain-driven bicycle from Great Britain quickly gained traction. With the adoption of pneumatic tires, the revamped bicycle was at last ready to deliver on its original promise to provide efficient, enjoyable — and reasonably safe — transportation. It soon toppled the old high wheeler and threw open the gates of the cycling kingdom to the general population.

Along with millions of others, Woodrow would get swept up by the great bicycle boom of the 1890s. But he was not merely following the crowd. “Mr. Wilson was not the sort of person to be infected by a craze,” Stockton affirmed. “But he found the bicycle a convenient way of getting about, both in this country and in England.”

Ironically, Josie gave up cycling about the same time that Woodrow finally took it up. Like many early wheelmen, Josie looked down on the safety with disdain. He found the design cumbersome and its low mount undignified in that it brought the rider so close to the dirt road. Nor was there any elitist pleasure to be derived from riding with the rabble. If he could no longer mount his “ordinary” with his head held high, it was time to give up the sport altogether.

Woodrow probably purchased his first bicycle around 1894, after he had returned to Princeton as a professor. For the next 16 years or so, even after the bicycle had lost its cachet, and even after he had assumed the university’s highest administrative post, Woodrow continued to rely on his bicycle to get around campus. A few years ago, a collector tracked down one of Wilson’s bicycles from this period, a chainless model.

While others were turning to various forms of motorized transportation, Woodrow remained true to the bicycle. One evening, a student was riding his motorbike through the distant outskirts of Princeton and spotted the university president dutifully pedaling his bicycle home. The surprised young man offered Wilson a tow, which the professor sheepishly accepted on the condition that he be released just before they reached the campus so that he would not risk being recognized or humiliated.

But it was while touring Scotland and northern England, home to many of his ancestors and literary heroes, that Wilson found true happiness on his bicycle. In early 1896, at age 39, Woodrow suffered his first stroke. Ellen urged her husband to spend his summer break in Great Britain riding his wheel so that he might regain his health. Woodrow thus embarked on the first of his three cycle tours abroad, at the peak of the bicycle boom.

Not surprisingly, Woodrow was not the only passenger aboard the Ethiopia bent on touring Great Britain by bicycle. Mr. and Mrs. Charles A. Woods of Marion, South Carolina, had also packed their wheels. The newfound friends agreed to reunite on land and cycle together.

The trio set off from Glasgow on their bicycles heading toward Carlisle some 100 miles southeast, just beyond the English border. Along the way they stopped in Ayr and Dumfries. Perhaps they were aware that they were traversing the territory of the late blacksmith Kirkpatrick MacMillan, alleged by the Scottish press to have built the first bicycle around 1840.

In Carlisle, Woodrow conducted vain searches for the church of his maternal grandfather (who had also been a minister) and the birthplace of his late mother. When he learned that the Woodses would be detained in town for a few days to repair a bicycle, Woodrow set off on his own by train for Keswick. He then rode his bicycle “16 enchanting miles” to his rendezvous with the Woods in Rydal, stopping along the way at Dove Cottage to tour the former home of the poet William Wordsworth.

After reconnecting with the Woodses in the renowned Lake District, Woodrow wrote to Ellen again, enclosing a tiny flower. He expressed guilt that he was having such a wonderful time without her. “It is hard not to envy Mrs. Woods [having] the daily sight of you, dear,” she teased him. “What I wouldn’t give for a magic mirror in which I could follow every detail of your journey.”

The trio continued southeast to York. From there, Woodrow cycled some 200 miles to London before taking a train back to Glasgow to board his homeward-bound steamship. He had enjoyed his first cycle tour immensely, especially his visit to the Lake District.

Three years later, in the summer of 1899, with Ellen’s blessings, Woodrow returned to Great Britain for a similar cycle tour. This time, however, he brought along Ellen’s brother Stockton. Woodrow even joined the Cyclists’ Touring Club so that the two could enjoy discounts at certain hotels and restaurants. His surviving club-issued Pocket Record reveals that his mount was an 1899 Columbia Model 59, purchased for $75.

Stockton quickly discovered that he could not keep up with his swift brother-in-law, even though the latter was 10 years the elder. Woodrow graciously insisted that they do most of their travels by train, with the bicycles stored in the baggage car. In this fashion, they toured Scotland before reaching the Lake District.

Woodrow wrote to Ellen that he and Stockton had just ridden along “the most beautiful road in the world” as they followed the River Eamont. He also described the “perfect” conditions they had enjoyed, including “keen fresh air out of the West [and] intense sunlight and quick moving shadows, showing every peak and line of the mountains, every sloping shore, every home, or group of trees or herd of cattle … ”

Most important, Woodrow assured Ellen, even though his cycling had been somewhat curtailed, his return to the Lake District was proving every bit as therapeutic as they had both hoped it would be. “An unspeakable peace rests upon this place,” he told his wife, adding: “[I feel] infinitely far away from all the world here in this tiny sequestered village.”

Stockton felt guilty that he was compelling Woodrow to cut back on his cycling, for he knew well that Woodrow “loved his bicycle, loved the rides along the fine British roads, and had looked forward to the ride from Edinburgh to southern England, all by wheel.”

Finally, once the two got to Surrey, in southern England, Stockton elected to stay put there for three weeks at the home of a friend so that Woodrow could spend his remaining time in England cycling on his own. Although things had not gone entirely to plan, Woodrow was still thoroughly satisfied with his second cycle tour in Great Britain.

In the summer of 1903, after having assumed the presidency of Princeton, Woodrow made his third visit to the Lake District. This time, however, because he had brought along his entire family, there would be no cycling. Nevertheless, he eagerly showed them many of the same awe-inspiring sights that he had first experienced as a cycle tourist.

Settling back in Princeton, Wilson stepped up his fight to “democratize” the university’s stodgy culture. Stressed out once again, he suffered a second stroke in May 1906 that temporarily deprived him of the use of one eye and one arm. That summer, the family set off again for another bicycle-free vacation in the Lake District to help Woodrow recover.

Some months later, in February 1907, a still-mending Woodrow took a solo vacation to Bermuda. There he met a divorced socialite named Mary Peck, and, unbeknownst to Ellen, the two began a torrid correspondence.

In late 1907, Woodrow suffered yet another stroke. The following summer, Ellen insisted that Woodrow spend his annual break back in the Lake District, but this time without his family. That would allow him to cycle his way back to health. But that was not her only reason to send him off on his own: she had become painfully aware of his relationship with Mary.

Woodrow admitted to her that his affair was “indiscrete,” but he insisted that it was “not improper.” He agreed, nevertheless, to abide by Ellen’s proposal. After all, now that he was in his early 50s and in the midst of a full-blown mid-life crisis, there was much he could ponder on a third cycle trip: his poor health, his troubled marriage, his three growing daughters, and his increasingly rocky tenure at Princeton — not to mention his as yet unfulfilled political ambitions.

Woodrow started off for the Lake District in the usual manner, docking in Glasgow and retrieving his bicycle. After brief visits to Sterling and Edinburgh, he took the train to Lockerbie where he began to cycle in earnest. He confessed to Ellen that he found his muscles “rather soft for the business of steady wheeling.” In Carlisle he sent Ellen a triumphant note. At long last, he had found at least the location of his mother’s birthplace, “under the castle walls.”

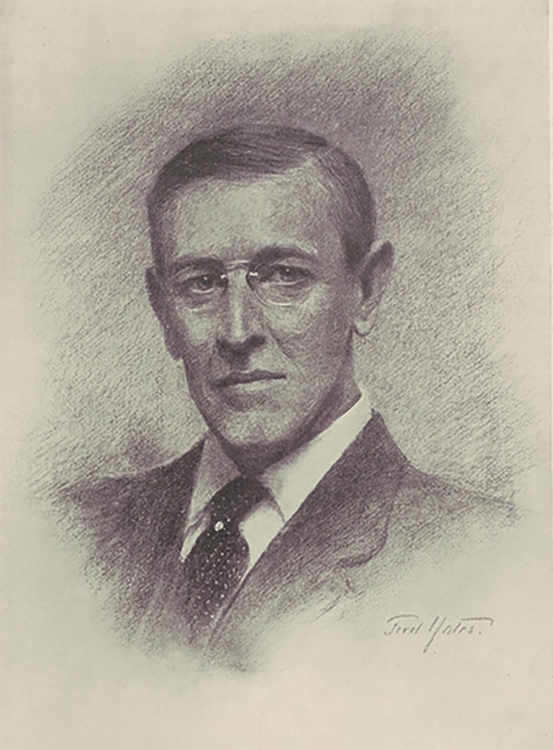

Reaching the Lake District, Woodrow dawdled there to socialize. By now he had cultivated warm friendships with a number of residents, including the local postman, a fellow cyclist, and Fred Yates, a portrait artist. Less than five years later, Yates would attend Woodrow’s first inauguration and make a pastel drawing of the sitting president.

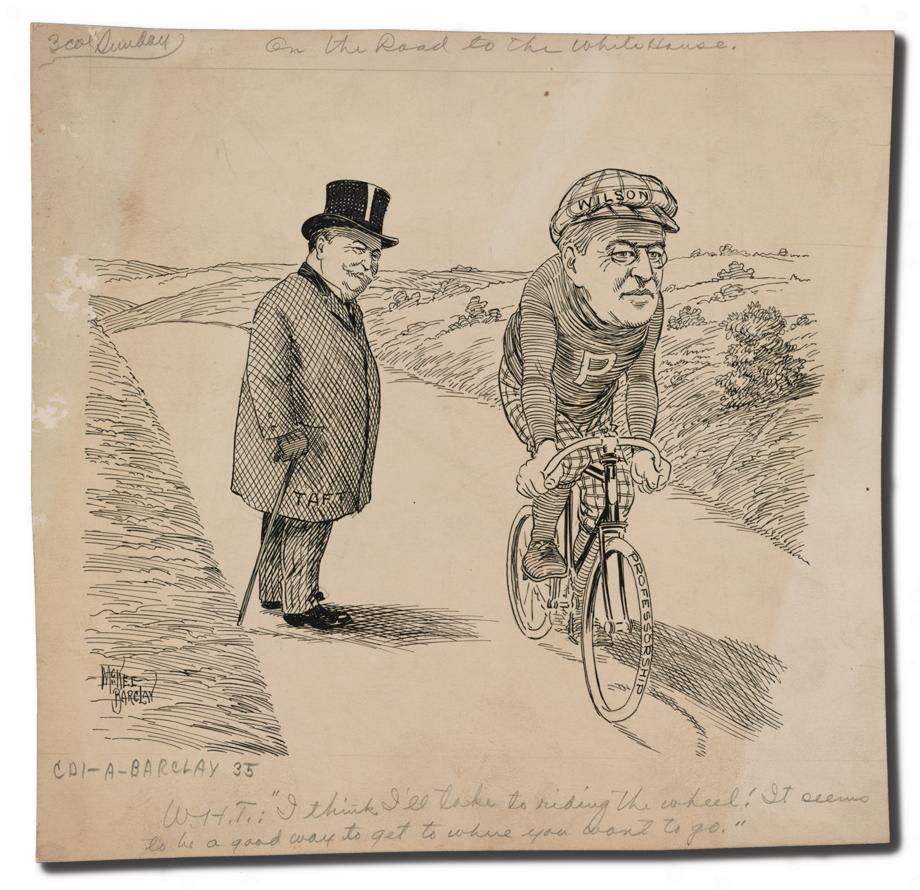

Woodrow returned to Princeton a fully recharged man, ready to repair his private life and get on with his professional career. Two years later, in 1910, he was elected governor of New Jersey and, two years after that, president of the United States. Running on a progressive platform that called for workers’ rights and an income tax, Woodrow won 42 percent of the popular vote, beating out the incumbent, William Howard Taft, and former president Theodore Roosevelt.

Of course, as he prepared to enter office, President Wilson’s passion for cycling was well known to the press and frequently lampooned, given that many considered the humble bicycle passé. One wit professed bewilderment “why a man who can run like Woodrow Wilson should want to ride a bicycle.” After rumors surfaced that Wilson’s running mate, Thomas Marshall, shined his own shoes, one commentator scoffed, “Well, why not? Woodrow Wilson rides on a bicycle, instead of [in] an automobile, every chance he gets.” Mused another: “Suppose Woodrow Wilson should ride his trusty bicycle up Pennsylvania Avenue on March 4?” If he does, chimed in another, “he will rank with Thomas Jefferson for simple manners.”

Despite the ridicule, E.M. Dodson, president of a motorcycle club in Washington, DC, saw the upcoming inaugural parade as a genuine opportunity to promote his favorite variety of two-wheeler. “If information circulating through the public press is correct,” he wrote the president-elect, “we are soon to induct into the presidency the first advocate of the two-wheeler, represented in your case by the bicycle. Such a signal event in the history of the sport should not proceed uncommemorated.” He pointed out, however, that there was no bicycle club in Washington “sufficiently well organized and equipped to offer themselves as your escort.” He proposed, therefore, to dispatch 50 of his own club members, dressed in their military-style olive green uniforms, to do the job. The president declined the offer.

In truth, President Wilson did indeed still cherish his bicycle. Be he also knew that, given his newfound fame and busy agenda, not to mention his poor health, it might be a long time, if ever, before he could cycle around town again or enjoy another relaxing bicycle tour. After assuming office, he became increasingly interested in the emerging automobile, a vehicle in which he could still ride while enjoying peace and solitude, albeit without the health benefits of cycling.

Yet he never lost his love for the bicycle, as one well-publicized incident from 1913 suggests. Riding up Pennsylvania Avenue on the evening of October 4 on his way home from a short outing, comfortably seated in his chauffeur-driven automobile, President Wilson suddenly heard a loud thud. After his vehicle screeched to a halt, the president realized to his horror that its wheels had narrowly avoided crushing the body of a telegraph messenger boy, who lay helplessly on the road beside a mangled bicycle.

President Wilson immediately sprang from the automobile and into action. “Are you hurt, my boy?” he blurted as he sprinted toward the victim. Without waiting for a reply, he hoisted the dazed boy to his feet and began to brush off his dusty clothing. “I ain’t hurt much,” stammered the boy at last, “but I just bought that bicycle yesterday, and it’s all broken.” The president told the tearful boy not to worry about that, he would get him a new one. The important thing now was to get him medical attention. President Wilson ordered his Secret Service men to take the boy at once to Providence Hospital in their car, and he placed his personal physician, who happened to be with him, in charge of the boy’s care.

A few hours later, back at the White House, the president was elated to hear that the boy — who turned out to be 15-year-old Robert Crawford — would be perfectly fine after a few days of rest to nurse his bruised body and twisted ankle.

At first it was not clear whether the president’s automobile had struck Crawford’s bicycle or vice versa. It soon emerged, however, that Crawford had suddenly veered into the president’s car while trying to avoid stones being thrown at him by another boy.

President Wilson nevertheless took full responsibility for the accident and stuck to his word. The next day, he visited Crawford at his hospital bedside. He told the awestruck lad that he would not only replace the lost bicycle, but he would also cover the wages Crawford would lose that week.

Upon his return home, the boy gleefully received his shiny new bicycle. He brought it to the telegraph station where he was instantly mobbed by his adoring mates and pronounced a “collision hero.”

At the close of his presidency, in the midst of intense peace negotiations, Woodrow Wilson reportedly told a confidante that the “dream of his lifetime” would be to cycle through France once he had left office. Chances are that the president had already sensed on the day he consoled the despondent Crawford that his own cycling days were over. At least he could encourage others more enabled than he to keep on cycling.

This story originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.