Riding Past the Edge of Instagram

Sometimes I wish I’d been born a century earlier. What a tremendous time it must have been for exploration — the infrastructure existed to travel to different parts of the world, but there was still plenty of mystery and room to discover things for one’s self. When David Livingstone stumbled onto Victoria Falls, he didn’t scratch his head and say with a touch of disappointment, “Geez, it looked bigger on Instagram.”

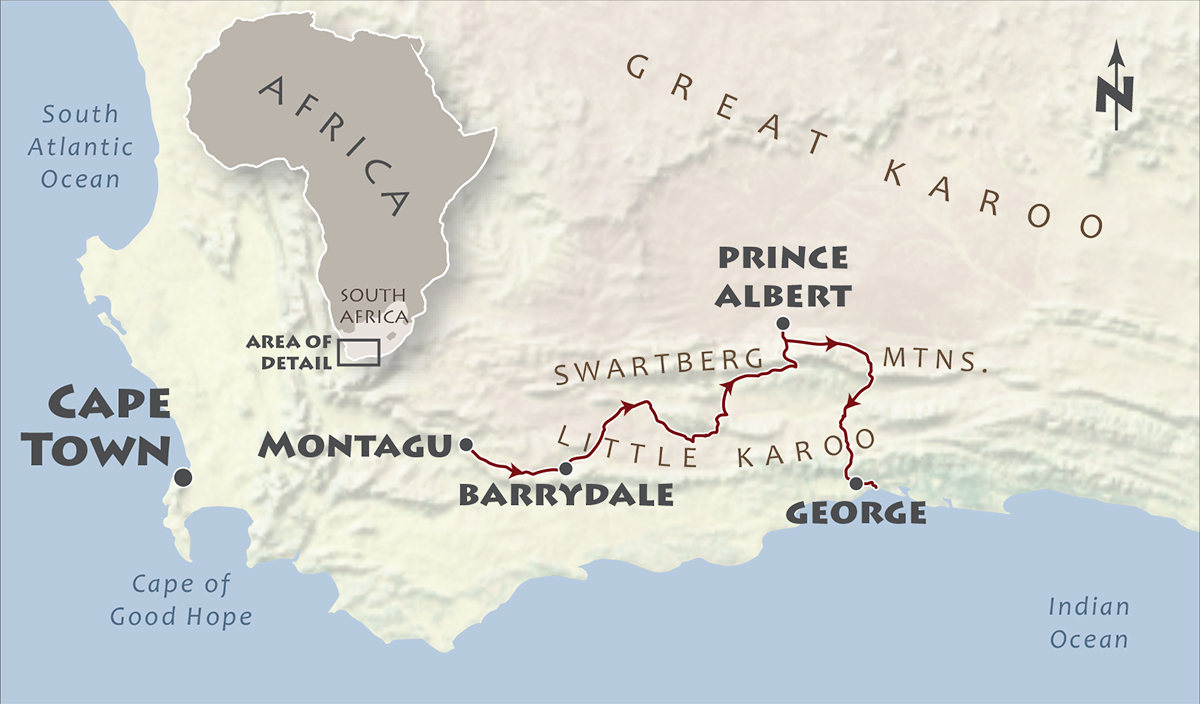

In spite of the information glut and the wealth of images available on the internet, even today there are some places that feel as if they still hold mystery. To me, the African continent is one of those places, and doing a bike tour in South Africa was an irresistible idea. Africa would be my fifth continent to explore by bike, and it felt different, more like terra incognita. I planned the trip with my girlfriend Nicky, and our goal was to spend two weeks riding through the Western Cape, mostly on dirt roads. Even with Google at our disposal, though, we had a hard time finding basic information about things like possible routes and towns to stay in. I was also a little unnerved by the common response from people when we shared our plan: “You know there’s a lot of crime in South Africa, don’t you?”

We were buoyed by the discovery of Bike & Saddle, a touring company based in Cape Town that operates bike tours throughout the country and, more relevant for us, offered us use of touring bikes. We reserved our wheels, and the rest of the trip details slowly fell into place.

Once we arrived and picked up our bikes, the owners, Gustav and Susanne, shuttled us to our starting point outside Cape Town. During the drive, they shared all sorts of local knowledge about not only bike touring but also the broader culture of the country. Moreover, they eased my fears about crime levels, pointing out that most of the crime is of the petty sort. “You’ll be fine,” they assured us. “Just remember to lock the bicycles.” The other advice they offered was to avoid riding in the heat of the day, between 11:00 am and 3:00 pm. Gustav encouraged us to take advantage of every bit of shade we could find. We were there in mid-summer when temperatures can soar well above 100°F. Cooling rains would be nonexistent as South Africa was suffering from a multiyear drought.

They dropped us off in the town of Montagu, a two-hour drive east of Cape Town. It was only 40 miles farther to Barrydale and our Airbnb for the night, so even though it was high noon and we’d be disregarding Gustav’s advice, we loaded our bikes and prepared to pedal off. There was a moderate to heavy breeze at our backs, and we’d be on pavement the whole way. “It should be a quick ride, two hours tops,” I said confidently. With that, Gustav and Susanne turned back toward Cape Town, and we pointed our bikes east and caught the tailwind.

“Crosswind,” I said. “It shouldn’t be too bad.” Five miles later, it was a straight-on headwind.

It was an exhilarating feeling, sailing through the town. The first day of a bike tour, riding in Africa … it felt great. Just as we reached the city limit on the far side of town, the wind shifted perceptibly. “Crosswind,” I said. “It shouldn’t be too bad.” Five miles later, it was a straight-on headwind. I started scanning for a patch of shade on the side of the road. Nothing. We pulled over so Nicky could adjust her packs and discovered that her iPhone was overheating. We commented on the temperatures but, really, it was only 30 more miles or so, just a few short hours of pedaling.

What we didn’t count on was that the road was going up ever so slightly. Meanwhile, the wind seemed to blow a little harder with every mile we covered. We passed a few farm stalls along the way, independent farms with a store or restaurant attached selling their produce, sweets, and drinks, but to our great disappointment, they were all closed.

Another half hour and I was struck by the thought that I really should have filled all of my water bottles before we started. We both were ready for a little shade as well. Soon enough, there was a sign depicting a picnic table and a tree. Perfect! We rounded a corner and there it was, a picnic table sitting in the blazing sun — but no tree. Where was the shade?! False advertising! Maybe this was the sort of petty crime Gustav and Susanne were talking about. Nonetheless, we pulled over, leaned our bikes against the picnic table, and left the pavement to crouch under a small shrub. There we were, among trash, heat, and an unrelenting sun, almost out of water and wondering just what we had gotten ourselves into (a sentiment common to most of my bike tours).

After having our hopes dashed by one more farm stall, fortune smiled upon us. The road tilted downhill, and in the distance we could see the town of Barrydale. Hallelujah! On the final stretch to our Airbnb, we went over some lessons about bike touring in South Africa learned on our first day: 1) the wind can, and will, blow from every direction at the same time; 2) it’s best to fill every water container before pedaling off; 3) distance signs in Africa might be an estimate; 4) signs advertising food options down the road can be misleading and lead to tears of anguish; and 5) African heat is a powerful thing.

We were riding through an area called the Karoo, a semidesert region known for its cloudless skies and extreme temperatures. The settlements and farming here are made possible by an abundance of underground water, but above ground the landscape looks pretty formidable, every variety of flora armed with thorns capable of piercing an unsuspecting traveler’s tire. Our plan was to traverse the Karoo in a northeasterly direction and then explore the Swartberg Mountains and their well-watered foothills before continuing south back to the coast.

The next day was to be our biggest push of the trip, an all-gravel route with no services along the way. When our Airbnb host mentioned that our intended road was frequented by snakes (cobras and pufferheads — I’m not familiar with the latter, but I sure didn’t like the sound it), and that a perfectly good paved road also led to our destination, it didn’t take much deliberation for us to change our course. Have I mentioned how much I dislike snakes?

Just as dawn broke, we were on our bikes and on our way. Early morning riding is where it’s at! We made great progress on the smooth pavement before the mercury climbed too high, but climb it did. When we came upon a farm stall — one that was actually open for business — even though it was only 10:30 am, we didn’t want to pass up the oasis. Settling in at a shaded outdoor table, we decided to take Gustav’s advice and see if we could milk our seats until at least 2:00 pm. I had a strategy all lined up: we’d order drinks and pore over the menu for a long time, feigning indecision. Then eventually we’d order salads, then a meal, then dessert, and finally more drinks. Our plan worked beautifully, but as the two o’clock hour approached, the air remained oppressively hot. By this point, the proprietors were chatting us up about our trip. When we admitted we were trying to stay out of the heat, they invited us inside to enjoy the air conditioning and stuffed us with more food, on the house.

A few hours later, and with three hours of riding yet to go, we changed back into our cycling clothes. When the restaurant manager saw us preparing to go, she insisted on driving us down the road a bit, at least to where the road turned to dirt. “Load up in the white bucket and we can go,” she said, pointing to a small pickup truck. A bucket! Nicky got in the front with her, and the manager’s six-year-old daughter climbed into the bed of the truck with the bikes and me. This girl was obviously an old hand at this — once we were up to speed, she stood atop a plastic five-gallon pail with her face in the wind, singing at the top of her lungs. I, on the other hand, crouched in the back, shielding my eyes from the onslaught of bugs. At one point, the girl looked back at me, then eyed a box next to her as if inviting me to stand on it. I smiled and went back to the arduous task of avoiding the bugs. I don’t think she was impressed.

Later on, I was disappointed to learn that she wasn’t calling the truck a bucket but rather a bakkie (pronounced bucky, more or less). The culture of riding in the back of pickup trucks, er, bakkies, is alive and well in South Africa. Most every bakkie we saw on the trip was hauling someone somewhere: kids to school, workers to the farms, families to church. In fact, when our benevolent chauffeur dropped us off to continue our ride, two women standing at the intersection climbed in and replaced me in the back of the truck. They all smiled and waved as they trundled off down the highway.

The five hours spent at the farm stall was offset by our early start, and we were still on schedule to meet Ralph, our next Airbnb host, at the intersection of two dirt roads and a windmill (try putting that into Google Maps). As we pedaled up to the intersection, there he was at the windmill, waiting to greet us. He and his wife Lynne had recently moved into an off-the-grid house just outside the town of Van Wyksdorp. Next to their home was another outdoor structure complete with a dining area, comfy couches, a dance floor, and a sign reading “Ralphie’s Tequila Shed” hanging from the eaves.

As we settled in, they invited us to join them for dinner. Over steaming bowls of homemade stew, we told them about our afternoon of hanging out at the restaurant, then getting a ride down the road. “That’s South Africa for you,” said Ralph. “People are so nice.” Turns out that was the case with Ralph and Lynne as well. As if the fantastic food wasn’t enough, Ralph brought out some of his finest tequilas for us to try. It was, after all, New Year’s Eve.

It was a heck of a way to usher in the coming year. We talked late into the night as the moon rose high above the mountains. Ralph is an avid cyclist and highly knowledgeable about the cycling culture in South Africa. We were already familiar with the Cape Epic, a multiday mountain bike race for teams of two. But that race, while the most iconic, was just the tip of the iceberg — there are cycling routes and events all over this part of the country. Before calling it a night, Ralph looked up at the skies and said there was a chance of rain overnight. It hadn’t rained in almost two years.

Hours later, I was awakened by a sound, and it took a few seconds to realize that it was the staccato tapping of rain on the roof. We’d brought them good luck! The drought was broken! Fifteen seconds later, the rain stopped — the first, and last, precipitation of our trip.

In spite of the late night, our alarm was set for 4:30 am to beat the heat. Ralph accompanied us for the first few hours, using his local knowledge to shave off a few miles with a shortcut. We parted ways at the top of a pass, where we began our cruise down a narrow gravel road toward the town of Calitzdorp and our next Airbnb. After a long descent, we leveled out onto a paved road that was lined with ostrich farms, one after another, each with hundreds of the enormous birds. Have you ever seen an ostrich up close? Really close? What strange creatures, with their high heels and awkward, prehistoric-looking bodies.

Given our sunrise start, we arrived at our destination by early afternoon. Immediately our attention was captured by an upscale vineyard surrounded by shade trees. With the exchange rate working in our favor, we each ordered a hefty glass of sauvignon blanc and browsed the lunch menu. My eyes grew big as they landed on the ostrich burger. Look, I pedal by cows all the time and have zero problem eating a hamburger, but this felt different. Maybe it was the wine affecting me, but it felt like I’d be devouring Big Bird’s cousin, or at least a family member of some bird I’d just made eye contact with. I stuck with the classic beef version.

I enjoyed the heck out of that burger, because I knew that food options would be minimal for the next few days. We were facing a long stretch of dirt road with few available services, a crux of the trip in terms of planning where to stay. Nicky had finally found a working farm with a few rooms to rent. The farm wasn’t located in a town per se, and when we got to the general area, there was no sign of it. Not to worry, though; we were promptly pointed in the right direction after asking the first person we saw about “Mandy’s place.”

Mandy welcomed us warmly as we checked in at the main house where the walls were lined with rows of old photos. When we learned that her family is the eighth generation of Dutch farmers to work this land, we couldn’t help but ask whether there’d be a ninth generation carrying on the family tradition. What we intended as a simple question led to a long conversation ranging from South Africa’s complicated history to the current political climate.

Although apartheid in South Africa only began in its official form in 1948, the centuries before that were marked by oppression and campaigns of violence against the native black Africans. The 1913 Natives Land Act restricted black occupancy to just 8 percent of the country’s available land, depriving the majority of South Africans of the right to own property, with predictable socioeconomic consequences. For nonwhites in present-day South Africa, unemployment is high and land ownership rare. Income inequality here is extreme, the highest in the world, according to the World Bank.

Since apartheid ended in the early 1990s, the South African government has been trying to make reparations for the historical inequalities and mistreatment suffered by many of its citizens. The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment program is one such attempt at righting past wrongs, giving hiring preference to black Africans, Indians, and other previously discriminated-against populations.

Two of Mandy’s three sons have graduated college with engineering degrees, and yet they’ve been unable to find jobs within South Africa, thanks, they suspect, to the affirmative action policies. Thus, they expect they’ll need to move to the UK to find work, leaving the family farm behind. The third son is finishing school in England and will then move across the pond to work on a large farm in North Dakota.

Mandy and her husband saw the writing on the wall and had recently sold the farm, though they kept their home and the guest house with its rooms for rent. It wasn’t just that there wouldn’t be a ninth generation working the land; they were also fearful of the farm being taken away without compensation. There’s been some talk of government-backed land redistribution, confiscating land from white farm owners and giving it to historically marginalized groups. The couple had watched that happen years ago in neighboring Zimbabwe, followed by hyperinflation and economic devastation. It wasn’t a sure thing in South Africa, Mandy said, but the potential of it happening, along with their sons’ employment struggles, was enough to make the decision to sell.

We ran into one of her sons later that evening, and he expressed his frustration at not being able to secure a job. Part of his vexation was that his family had been in the country for so long while people migrating from other parts of the continent would qualify for openings before him. What he said made sense, but we’d also seen the townships with their rickety shacks as we’d rolled through the outskirts of larger cities, witnessing firsthand the disparity in living conditions between many black and white South Africans. The country’s situation is complex, and the only thing I know for sure was that, as bicycle tourists, we were treated equally well by everyone we came across, regardless of their history or circumstance.

Leaving Mandy’s the next morning, we put politics out of our minds to focus on the ride over the famed Swartberg Pass, a winding dirt road that climbs 3,000 feet as it crests the Swartberg Mountains. The northbound descent from the top was a just reward for our efforts, serving up miles of coasting through geologically spectacular roadcuts before delivering us into the town of Prince Albert. Friends of mine who rode across South Africa the year before suggested that if we stop in any town, it should be this one. Prince Albert is a tourist hub in the middle of the desert, full of restaurants and art galleries, superb cheap wine, and ice cream. Although we appreciated the decadence, in truth the culture and grit of the rural areas held more appeal for us.

We pulled out of Prince Albert at 4:00 am, leaving early both to avoid the worst of the heat and to allow extra time for the climb. We had one more pass to traverse: Meiringspoort Pass, a paved road through a river-carved canyon connecting the two main subsections of the Karoo. In prehistoric times, the whole of the northerly Great Karoo was an inland lake, with the Swartberg Mountains acting as a natural dam to the south. On the southern side of the mountains was, and remains today, the comparatively minuscule Little Karoo, a strip of land running east to west. Over millions of years, the lake lapped against the mountains, eventually eroding a pathway uniting the Karoo. Construction of the serpentine road through the river valley was a major feat of engineering and was instrumental in opening up the Cape Colony to inland trade routes.

Pedaling alongside the river, we had two hours under our belts before seeing a single car. The road curved past vineyards and lush, expansive farms; it felt like Eden. The verdant foothills of the Swartberg range were a stark contrast to the desert-like conditions we’d experienced for most of the trip. Traveling over Meiringspoort Pass from north to south meant we had more downhill than up, and if that wasn’t enough, there was a steady wind at our backs carrying us through this paradise.

As we continued to the coastal town of George over the next few days, we marveled at what great riding, and touring, the Western Cape has to offer: limitless roads, friendly people, and an abundance of history, culture, and wine. Nearing the coastline, we spotted a touring cyclist approaching from the opposite direction, the first bike traveler we’d encountered on our trip. He was riding something called the Cross Cape Route, a recently developed and mapped by the Western Cape governments and local municipalities to promote tourism. With maps printed from the project’s website, he was midway through the 700-kilometer mostly gravel route.

I must say that hearing this made us happy. Traveling by bike is our favorite way to explore new destinations, and it’s always great to see bike tourism promoted. But, more than that, learning that an official route existed — and we hadn’t taken it — heightened our appreciation for our own adventure. Discovering the Western Cape by cobbling together a route from fragments of information and tips from the locals, we felt like intrepid travelers from a bygone era, finding unexpected — and un-Instagrammed — sights around every bend in the road.

Tom Robertson is a freelance photographer and a cycling and adventure enthusiast based in Missoula, Montana. He was a cartographer at Adventure Cycling for 14 years. Follow him @tomrobertson4.

South Africa Bike Center

On the outskirts of Cape Town lie sprawling developments across what’s known as the Cape Flats. These townships, as they’re known, filled us with so much curiosity about their origins, the residents, and the experience of living there.

It turns out that Gustav and Susanne of Bike & Saddle Touring Company, the folks who rented us bikes, run a half-day bike tour of Khayelitsha, the largest and fastest-growing township in Cape Town. The outing is a window into life in a township and the trials of living in a postapartheid South Africa. We signed up for a tour led by Skeezo Vitzo, a longtime resident of Khayelitsha. As luck would have it, three coaches from the Velokhaya Life Cycling Academy also joined our tour as “bonus guides.” The academy uses cycling as a way to empower youth, teaching important life skills like discipline and teamwork by offering after-school activities in a place where such things are rare. Some of the participants have even gone on to professional racing careers.

As we pedaled around, our guides spoke about the challenges of cycling in the township as well as the opportunities it can bring. It was as much a culinary tour as a cultural one, with our pack stopping at different market stands to sample the local foods — including sheep’s head — while taking in the music, traditional healing, and vibrant, bustling market center.

We felt right at home recounting past rides and bike-related experiences with our new friends, proving once again that the bicycle can be a great equalizer.

This story originally appeared in the December 2018/January 2019 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.