Following the Monarchs

On Day Four of my bicycle adventure, near the summit of a 6,000-foot climb in Mexico, I saw my first migrating monarch. She chased pockets of evening sun as clouds soared above, blurring the edges separating lonely highway, humid forest, and expansive sky. More than beautiful, the flicker of her stained-glass wings was reassurance. My trip was not impossible. After months of planning, I was doing what I had set out to do.

I was following the monarch butterfly migration by bicycle — butterbiking with the butterflies.

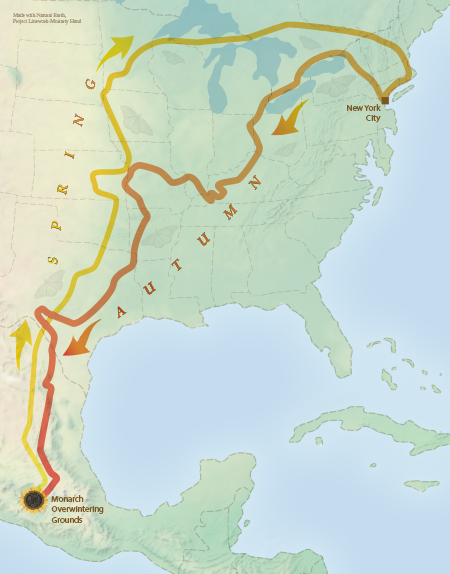

The monarch migration is often referred to as one of the planet’s most incredible events. It takes three to five generations of butterflies to complete the annual loop, from Mexico to Canada and back. Each fall, the monarchs that fly thousands of miles south to Mexico are the great-grandkids of those that flew north from Mexico in the spring.

Knowing this, and knowing that they and their speck-like eggs, lumbering caterpillars, and emerald green chrysalides can survive the dangers of nature and man, to connect mountaintops to prairies and ancestors to descendants, amazed me. Following the monarchs — learning from them, teaching about them, being part of their adventure — left me reverent. Unlike with a magic trick, the more secrets I uncovered, the more spellbound I became.

My mission was to be a voice for the monarchs…

I chose to follow monarchs because, as a cyclist, educator, scientist, and conservationist, they were the perfect storm of possibility. Flying about 60 miles a day (although one has been recorded flying 265 miles in a day!) and spreading out in the millions across a landscape traced with roads, they were the perfect (and perhaps only) migration I could follow by bike. At home in backyards, school gardens, parks, roadside ditches, and the wildest reaches, monarchs, like clouds, are democratic in their reach.

Well studied yet posing many unanswered questions, monarchs are the perfect teachers to showcase the power of nature and science. Threatened with extinction, they were the motivation I needed to use my body, time, voice, and bike to contribute to the conservation movement.

Leading up to the official first mile of my trip, I spent three months in Mexico waiting with the overwintering monarchs for spring to come. Ten thousand feet above sea level, the cold, quiet forest, dripping with monarchs, was divine — a temple made by trees and worshiped by a congregation of wings folded in prayer.

In March, when the sun’s warmth had begun to pour through the branches and send the butterflies into fluttering eruptions of orange, it was time to start. By then, the monarchs crowded the skies, and I felt the anticipation in their swirling flight. I loaded down my beater bike, dinged with past adventures, and rode into battle — the battle to save one of the world’s greatest migrations.

Because scientists believe that monarchs navigate through Mexico by following the Sierra Madre Mountains, that was where I aimed. On a road littered with potholes and speed bumps, I coasted through the first mile, soaking up the hazy views of my mountainous future. Ideally, I would have followed those mountains and the monarchs straight to Texas, but it wasn’t that easy.

Monarchs don’t follow roads, and roads rarely follow mountains. I was left to piece together a route crisscrossing the spine of the range. A collection of miles led me either slowly uphill to forest crowns or slowly downhill to the mountains’ hot desert shores. I used nearly every hour the sun gave me to ride and every small town to refuel. The slow pace was sustained by impromptu offerings of ice cream, glass bottles of ice-cold soda, homemade popsicles, my daily mango quota, and Mexico’s open arms.

Too often vilified, Mexico was the hero in my story, which should be no surprise to any cyclist who has pedaled against the warnings and found a softer truth. Every few days, after asking for directions or explaining my monarch adventure with broken Spanish, I was given generosity. When asked if I wanted tacos, I said, “Si.” When asked if I wanted to stay the night, I said, “Si!” On an adventure, saying yes is as important as drinking water or carrying a patch kit. Although you cannot predict when, who, or how you will be rewarded, you can count on the opportunity.

Cycling north, I continued to let the monarchs decide my route. They led me through places I might never have gone, places I wished I hadn’t gone, and places full of both bold and humble beauty. Unlike most bike tours, the monarchs led my way.

In Texas, spring burst with wildflowers: paintbaskets, winecups, and lupines stood captivated by the sun and invited even the most timid pollinator to waltz among their petals. In Oklahoma and Kansas, the spread of migrants towing warmth and color from distant lands in the contrails of their feathered, scaled, and hairy wings mesmerized me, as did the hibernators that let out long sighs as they stretched among the sun’s rays before shaking off the last grasp of winter. I was surprised to find such drama along midwestern roads.

Iowa, Nebraska, and much of Minnesota offered a tour of corn. Long rows of tiny corn starts, poking above the earth, stretched from horizon to horizon. Those miles let me see our planet as butterflies do. Although the hospitality was unmatched and the efforts of those fighting for a future full of monarchs was as fervent as in any place I’d been, it was in those miles that I found a pain far beyond headwinds or steep hills. I saw the reality of our choices. I saw that for the monarch to have a future, we have to change.

The monarch population has been declining dramatically for 20 years. Each year, because of habitat loss and climate change, the number falls steadily. Millions of monarchs are now missing from our skies. Pausing from riding, I heard the same story a hundred different ways. “When I was a kid,” the story would begin, “we used to see thousands of monarchs.” I would listen, my heart heavy, and then challenge them to examine why that was true.

Restoring the prairie and planting milkweed (the only food source of the monarch caterpillar) was my rallying cry, and education was my medicine. Beyond roadside conversations, I presented this message to over 9,000 people at schools and nature centers. My mission was to be a voice for the monarchs, to empower everyone to be scientists with garden laboratories, to show boys and girls that they could ride bikes and catch bugs, and to remind North Americans that we are connected by butterflies.

Reaching the near-northern edge of the monarchs’ range, I headed east, dipping into the freshwater waves of the Great Lakes, marveling at hummingbird hawk-moths and curious skunks, finding hospitality and ice cream at regular intervals, and finally arriving for a swim in the Atlantic Ocean. I followed the ocean to the Brooklyn Bridge and merged into the chaos of New York City.

As the buildings, noise, and traffic engulfed me, I saw my entire trip unfold. It seemed impossible that by cycling I had connected a forest in Mexico — where the hum of butterfly wings had floated through a skyline of trees — to the hum of humans below New York City’s skyline. From Point A to Point B, every trip is at first only lines on a map, but if you carry on, the lines transform into miles. Miles, stories, memories, life.

Reaching New York City, I spotted proof that monarchs need nothing more than green space. In a bunch of purple flowers, almost entirely swallowed up by pavement, I spotted a monarch. Like an offering, he spelled out hope, a request for a shared planet. He taught me that it doesn’t matter where we plant gardens, only that we do. If we share the earth, the monarchs will come home.

From New York I pedaled indirectly, letting my route pull me north to the spray of Niagara Falls, east to the southern tip of Ontario (which acts like a funnel for migrating monarchs), and finally south through Ohio, Indiana, and Missouri. My route continued to link invitations, monarch hot spots, and guesswork. Using Google Maps, I picked the quietest backroads, aimed for public lands, and found that most nights I could tuck off the road behind rural churches, between corn rows, at the far edge of weedy cemeteries, and under the protective canopies of less tamed woodlands. The rest of the nights, I was invited inside.

I may have been cycling solo, but thanks to the passionate team of monarch stewards across North America, I was never on my own. “The monarch network rallied, and just as they organized to feed, house, and save the monarchs, they organized to feed, house, and help me save these butterflies.

When the future seemed empty, the monarch network’s commitment gave me hope and let me dream big. As I pedaled, I dreamed of a time when every house, school, and community had butterfly gardens, allowing native plants and milkweed to rewrite the rules on what beauty is. I dreamed of monarchs thriving as our neighbors, linking us all, and helping us discover the tiny secrets buzzing, droning, and whirling in flowery coves, grassy edges, and wilderness expanses. I dreamed of unborn generations that could hop onto bikes and wander toward prairie horizons as butterbikers.

On a bike tour, miles are shorter when we are riding toward our dreams.

My fall migration was a dash through Kansas, Arkansas, and Texas, with pauses just long enough to move walking stick bugs off the roads, catch snakes basking in the sunshine, chase monarchs with my camera, give presentations, tour gardens, interview with reporters, swim in limestone-steeped waters, and slowly watch the prairie transition to scrubland. Reaching Mexico once again, I aimed, like the monarchs, for the Sierra Madre Mountains.

I arrived in Mexico behind the main migration, a straggler. It was not a surprise. I had already learned that I was slower than the butterflies. Still, I saw monarchs daily and was able to join a pilgrimage of yellow sulfur butterflies floating like cottonwood seeds in the wind. Together, with the plethora of butterflies that sprang from the skies like fireworks, we formed a parade of color.

I ended my trip after 10,200 miles by climbing a steep cobblestone hill. I’d saved the hardest part of the trip for last. Breaking through the sweaty slog, a monarch wandered across the sky. She passed effortlessly overhead, proving once again that monarchs are tougher than cyclists. I stopped, caught my breath, and gauged my progress. “Almost there,” I told her.