Final Mile Anthology

This article first appeared in the August/September 2021 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

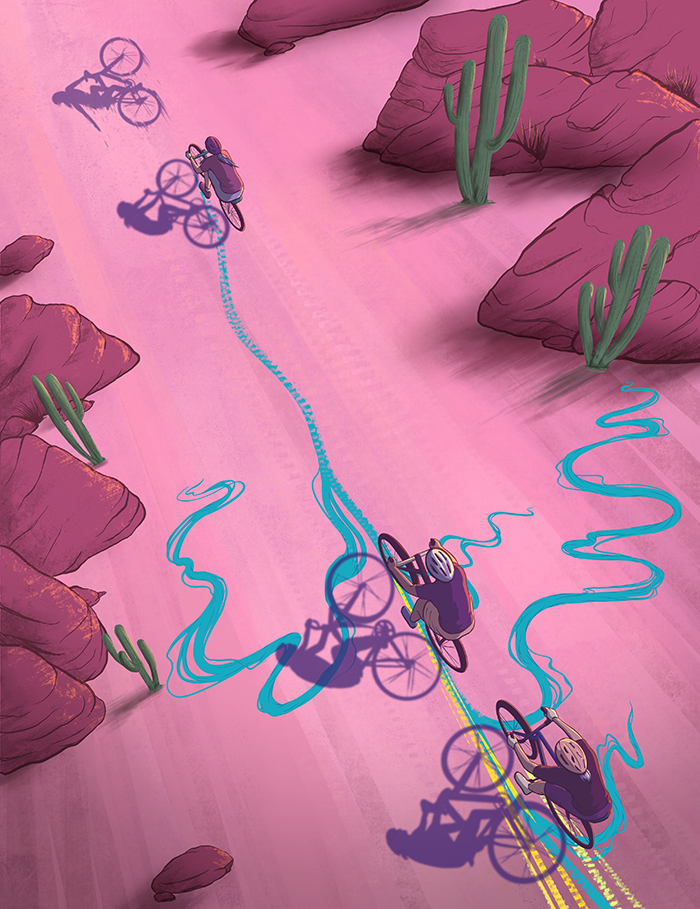

First Family Bike Tour

by Aziza Bayou

Though the road is rocky, sure feels good to me

And if I’m lucky, together we’ll always be

I hummed the tune “Rainbow Country” by Bob Marley and the Wailers as we rolled along a gravelly portion of the trail. Like a well-worn talisman, I sang the same lyrics on repeat as the sun bore down on my back and my bike trailer resisted each rock I encountered.

My husband Marc and I and our two young children (a one-and-half-year-old daughter and a four-year-old son) were on our first official family adventure cycling trip, from Cumberland, Maryland to Washington, DC, along the C&O Canal towpath, and we had gotten off to a bumpy start.

Our route covered 185 miles over four and a half days in early June 2020, staying in lodging near the towpath along the way. We planned a generous itinerary to allow space for fun and a cushion for the unexpected. This was our entrance into the world of family adventure cycling, and we wanted it to be a pleasurable experience for all four of us.

This wouldn’t be the three-month-long bike tour of our pre-married lives when Marc and I cycled from Finland to Italy — spontaneously deciding when and where to stop, camping in a potato field in Germany and frying the freshly-harvested leftovers, soaked to the bone and satisfied after a full day of rain in the Netherlands, rolling through the open mountain meadows of Switzerland, counting mushrooms in Sweden.

On that trip, we carried only what we ourselves needed, and did or didn’t do only what we ourselves wanted. This C&O Canal trip with our two kids was a different kind of adventure.

On our pre-married adventure cycling trips, we had often stayed up too late and lingered in our sleeping bags as the morning grew warm, leisurely repacking our panniers while sipping coffee. On the first day of this family trip, we were raring to go after sunrise cries and cuddles, hastily repacking among a flurry of breakfast and re-helmeting four heads.

In my eagerness to pack well, I had maybe overpacked just a tad, but with two young kids in tow, I was trying to be prepared! Extra pants, extra snacks, and extra wipes meant a lot of extra weight. We started with both kids on Marc’s bike, using our two-child Weehoo. After some fussing from the baby, we transferred some of the gear in my Burley trailer onto the Weehoo and moved the baby onto the trailer to ride with me. It didn’t work. I was struggling to keep up, and our daughter shrieked from her cozy enclave with each pedal stroke. With each of her screams, my leg muscles shouted back in response. No changes we tried worked to soothe her, and I was mentally and physically maxed out. First Family Bike Tour, Day 1.

As we rolled into our first night of lodging, I wondered how I’d be able to care for our energetic children and meet my own needs after riding double those miles in the following days. I told myself to stay in the moment, that I only needed to think about each foot pushing the pedal each time. Yet my mind lurched ahead to the challenges I saw down the road.

After the kids went to sleep that evening, I decided to relinquish control and trust the process — to be in the moment as much as possible and presume that solutions would arise. Not knowing how the rest of this trip would go sounded a little unnerving to my mom-mind, which had adapted to routines and predictability, but that’s the “adventure” part we were seeking, right?

This C&O Canal trip with our two kids was a different kind of adventure.

I woke up the next morning determined to embody the guidance I often give our four-year-old, to have a positive attitude and view obstacles as stepping stones from which to heighten my vantage point. As I fed and clothed the children, Marc concocted a new cargo setup that attached much of my load to his. The two-child Weehoo and single-passenger Burley trailer filled with our belongings were now both attached to his bike — engine, passenger car, caboose. He hauled with joy the majority of the weight that had impeded me from keeping pace that first day.

Ah, what a metaphor for marriage! Equilibrium isn’t in carrying the same weight regardless of strength, but finding the balance that helps everyone move forward together. He yoked my burdens to his with a smile on his face, always happy to crank any way and any how. He had the two most important passengers in our world in tow, and he loved every minute of it. And on that second day, the baby showed how quickly she had adapted to her first bike tour and sat like a Buddha in her seat, just like her big brother in the seat in front of her.

The rest of our trip went on like this: the dappled sunlight sending warm beams through the green leaves, the crunch of our tires along the gravel, a placid breeze caressing our faces and the swaying trees. Even though civilization was so near, we were in refuge, the masks and anxieties of COVID-19 feeling a world away. The occasional fellow reveler we saw would often greet our little train with a smile upon seeing our two little ones enjoying the ride.

As we took our lunch break in the grass by the Potomac River on a magically breezy, just-warm-enough day, our children were fully engaged in spotting insects on a tree, and the closer they looked, the more diverse and fascinating insects they found: beetles, arachnids, ants, and winged ones too. Whether on the bike or off, they were absorbed in their surroundings at each moment, trusting their needs to be met as they arose, not questioning what we were doing next or why we were even doing this at all.

On previous trips, we had taken in the sights through the filter of our own interests, but this time we were guided by the interests of our children. “Look, an owl! Hoot hoot!” The excitement was palpable for us all as we spotted a young owl flying so close over our heads, perching a mere 12 feet away. We squealed with glee over a snapping turtle making her nest to lay eggs, or a herd of deer bounding across our path. We made up silly songs about the wildlife we saw; counted birds, turtles, snakes, and groundhogs; and gave math problems to our four-year-old about squirrels and their nuts. We were a team, and we moved through the world together at a perfect pace for us.

This was it. There was no running around trying to multitask, send emails, or clean the house. It was simply being together, observing our surroundings, bathing in the beauty of our children discovering this world. We didn’t need to go far from our northern Virginia home to do this; we simply needed to pay closer attention, to see life as they do from their young eyes.

As we rode along, “Rainbow Country” arose again in my mind with an apropos refrain:

I feel like dancing, dance ’cause we are free

Our family was free in the world, our little bike train taking in all the moments as one.

And if I’m lucky, together we’ll always be

Aziza Bayou is an anthropologist and adventure cycling enthusiast residing in Fairfax, Virginia. She teaches anthropology at George Mason University and is a wife and mother of two. In her free time, she writes poetry, cooks, dances, reads, and of course rides her bike.

Pedaling for Love

by Bill Kavanaugh

The year was 1977. My best friend Jeff and I had just finished our junior year of high school. All year, we’d been hopelessly smitten with two girls who also happened to be friends. In our single-minded pursuit, we had overheard that the girls would be vacationing on Cape Cod in August. I had vacationed on the Cape before and knew it well. Jeff had never been and was keen on going. Most of all, we wanted to spend time with these girls.

The plan was to borrow my family’s rusty Plymouth, but the alternator was shot and my father was against the idea. Disappointed and somewhat peeved, we were determined to get there. And after days of brooding, we conceived another plan.

We would run away from home, cycling to the Cape on 10-speeds. I would rise at dawn, slipping out of the house before anyone noticed. I would leave a letter in the mailbox explaining where we had gone, telling my parents not to worry and when to expect me back. The only outsider privy to the scheme was my little brother, whose job it was to nonchalantly wander down to the mailbox and “accidentally” discover the note, presenting it to my parents.

We would ride 100 miles daily, using folding maps for directions, and arrive on the Cape in three days. This would leave plenty of time to locate the girls and hang on the beach. I say locate because we only knew the town where they were staying and — more importantly — they were unaware of our intentions. In our blissful, hormone-fueled naiveté, we planned to just sort of show up and surprise them. We imagined their reactions as we proudly rolled onto the beach:

“Wow! You rode all this way just to see us,” they would sigh. And, POOF, we would be heroes.

Then we would enjoy long afternoons, admiring them in their bikinis. And soon they would realize what irresistible, charming guys we were and we would leave for home rested, tanned, and going steady.

Of course, the girls didn’t know how much we liked them, and we had no idea whether they even liked us. Also, we had only a sketchy route based on outdated maps. There were no support services, no mirrors, no helmets. Our repair kit consisted of a wrench, pliers, screwdriver, tire irons, and a spare tube. Shorts, T-shirt, and sneakers were the basic attire. And in 1977, there were no cell phones.

Out in the garage, my Raleigh Grand Prix was ready to go. Strapped to the rear rack were a tent, sleeping bag, and other basics. A few miles down the road, Jeff was eagerly waiting with his Schwinn Varsity Sport. Weighing in at a sluggish 40 pounds, there was nothing even remotely sporting about his bike. It was 100 percent U.S. steel, built like a tank. My British Raleigh was a bit more refined and about 10 pounds lighter. But neither bike had seen fresh grease since leaving the factory, and that was years ago.

We set off, spirits high for the adventure of the open road ahead.

And, POOF, we would be heroes.

For the first 20 miles, we rode briskly south along the scenic Hudson River to the Bear Mountain Bridge, part of the Appalachian Trail and the only local crossing allowing pedestrians. From there, we traversed the winding backroads of New York before crossing into Connecticut.

We passed most of that sweltering afternoon pedaling through the rolling countryside, passing quaint, peaceful villages with picket-fenced yards and along lonely, meadow-filled byways brimming with buzzing locusts and softly chirping crickets. But among this bucolic tranquility, things began to go wrong.

We had packed only a water bottle each, a woefully inadequate supply even for two indestructible teenagers. Jeff was a pole vaulter on the track team, with thighs like utility poles. I was a distance runner, light and lean, built for the long haul. As the miles ticked by, I remember noting Jeff’s thighs, the muscle strands bulging beneath the skin like thick cables of steel. Although these were powerful legs, they were not prepared for the relentless, grueling strain coupled with a lack of fluid. Soon the powerful legs began to cramp, causing us to stop several times. Once we encountered a country store, we indulged on soda and snacks, mitigating the damages temporarily. But there were other challenges too.

Bikes of this era were commonly equipped with crude derailers that were notorious for imprecise shifting. Moving the lever even slightly resulted in a loud clanking sound, reminiscent of some menacing industrial machine. Since the chain was moved by friction, one was never sure what was going to happen when engaging the lever. Often the chain jumped wildly, traversing several cogs, landing on a gear unlikely to be useful. Shifting while climbing was a particularly daring maneuver as the chain occasionally slipped before settling into a cog. If the rider happened to be standing while this occurred, or nudged the lever accidentally, there was the threat of some unpleasant and possibly permanent consequences.

It was almost dark when we wearily rolled into the outskirts of Waterbury, Connecticut, over 100 miles from home. We saw no campgrounds nearby, and there was no one around to ask. But we needed somewhere to sleep. Then we spotted a lonely cemetery. It wasn’t ideal, but it was a clear space and unlikely anyone would bother us there. We erected the tent, ate some provisions, and quickly joined the deep sleep of the dead.

We were awakened in the dark of early morning by torrential rain, which quickly penetrated the tent and created ponds on the floor, mostly beneath our bedding.

There are moments in life in which words cannot express the despair of a particular situation. Indeed, this was one of those times. And there, lying in saturated bedding, the mission again changed tack, and we conceived a plan of even greater brilliance.

We would cycle home and propose a deal to my father: in trade for the car, we would install a new alternator, as Jeff was a competent mechanic.

“Can you do it?” I asked him.

“Piece of cake,” he said with a smile.

To save time, we would cycle Interstate-84. I-84 was, and still is, strictly off-limits to bicycles for obvious reasons, but we were beyond caring at this point. With renewed optimism, we broke camp and headed home. It was 6:00 AM.

Donned in ponchos and buffeted by incessant wind and spray, we made excellent time on the interstate’s generous shoulder and mild gradient. We traveled mile after mile at spectacular speeds. No sign of police, no need to stop. Things were going well, which is almost always a sign something is about to go wrong.

Highways are constructed with expansion cracks cut into the pavement. These cracks run perpendicular to the direction of travel, but at ramp entrances, the crack becomes parallel. In the speed and excitement of our progress, among the pelting rain, I did not see the crack until it was too late.

The last thing I remembered was catapulting sideways through the air, holding tight to the bars like a patron of some wild amusement park ride, before slamming onto the pavement, accompanied by the sound of grinding metal. This was immediately followed by a horn and howling tires as a car swerved within inches of me before accelerating up the ramp. Shaken and bruised, we continued on.

By noon, the sun was shining and we were at a phone booth at the Newburgh Bridge, about 10 miles from home, calling my father to pick us up. My parents were calm people. Although they loved me dearly, my father never reported my disappearance to the police, probably because he had done similar things at my age and in those days, people didn’t seem to freak out about such matters. However, our disappearance did succeed in sowing enough guilt that he agreed to loan us the car. Two days later, we arrived on the Cape.

Ironically, the only surviving relic of this trip is my water bottle. It sits on a shelf in my bike room — a grave reminder of the importance of hydration.

Just in case you were wondering, neither of us got the girl.

Bill Kavanaugh is a freelance writer living in central Pennsylvania. In addition to cycling, he enjoys fly-fishing, gardening, and a small collection of vintage British 3-speed bicycles.

Wild Camping in Woss

by Denise LaFountaine

My Warmshowers host at Campbell River told me I would now be entering the more remote part of Vancouver Island. “You might have to wild camp,” he said. I knew I would have to camp in the wilderness on my solo ride from Seattle to Tuktoyaktuk, on the Arctic Ocean, but I didn’t think it would be so soon.

I rode up to the gas station and general store in the small hamlet of Woss, 80 miles north of Campbell River. I bought a bag of chocolate-covered almonds, connected to wifi, and sat outside the store in a folding chair while I Googled nearby campsites. From what I could gather, there was a campground five miles out of town on an old gravel road. I asked an elderly gentleman filling up his truck if he knew how to get there. “Hmm, I’ve never been there, but I don’t think it’s far.” I asked a lady coming in to buy cigarettes if she knew. She looked around and said, “Nope.”

I walked back into the store to ask the attendant. “Excuse me, do you know where the camping is in town?”

“Yes, it is down the road,” he said.

“Down the road where?”

“I don’t know,” he answered in a thick Chinese accent. “I am new to the area. I bought the store two years ago.”

Behind him was a local gentleman who overheard the conversation. “Are you looking for a place to pitch your tent?”

“Yes,” I said, scoping the man for the tell-tale signs of a serial killer.

“Follow me. You can put your tent up in the field at the elementary school.”

I followed him despite knowing full well how this would all play out. I’d seen one too many episodes of Dateline to trust this seemingly good-natured man. Nevertheless, I followed his white minivan two miles down the street, around the corner, and through a residential area to a giant field with an oval running track beside an old boarded-up elementary school at the edge of town.

“You have the entire field to yourself,” he gestured with a big, friendly smile. “Have a nice evening!” he shouted from the window as he drove away. I waited until the minivan was out of sight, then headed over to the abandoned school. I wasn’t going to be a sitting duck in the middle of that field. I walked around the school until I found a sheltered area in the back situated just feet from thick, dark woods. I leaned my bike against the wall, squatted down, and studied my surroundings as if tracking a pack of wolves.

I knew I would have to camp in the wilderness on my solo ride from Seattle to Tuktoyaktuk, on the Arctic Ocean, but I didn’t think it would be so soon.

Vancouver Island has the largest population of cougars anywhere in North America and one of the largest black bear populations. I talked to a wildlife ranger in Campbell River who said that a grizzly had swum from the mainland and was spotted near Port McNeil just 47 miles away. The space between the covered area where I sat crouched and the beginning of the forest was a stone’s toss away. I imagined any number of wild animals sizing me up, ready to pounce as soon as the sun set, which was very soon.

I jumped on my bike and rode straight to the convenience store. I plopped back down on the lawn chair to decide what to do next. In an hour, it would be completely dark. I was too tired to figure out how to get to the campsite. Dark clouds had formed and a light drizzle moved in; I had to act fast.

Over the past 10 days on Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula, I had either stayed at a campground right off the highway or with a Warmshowers host, living the good life of an urban bike tourer. I barely had to put up my tent or pull out my stove. The reality of the wilderness caught me off guard. Had I done my research and left town earlier, I wouldn’t be in this predicament, but remorse wouldn’t save me now. I came up with a plan. I went back into the store to talk to the attendant.

“Um, excuse me,” I said.

The owner came out from the back room.

“What time do you close?”

“10:00 PM,” he said.

“Could I sleep in here tonight?”

The owner stared at me, his eyes ever widening with a slight hint of fear.

“Could I just lay my mattress out in the back of the store and sleep in here tonight?” I asked again.

“You want to sleep in the store?” he said, tilting his head sideways.

“Yes, that’s right.”

“Oh no, so sorry. You cannot sleep in the store.”

I pointed to a corner where I would be out of the way. “I have my own food.” I reassured him.

“No, no,” he laughed nervously.

“Can I sleep outside of the store?” I asked when I sensed he was feeling for an emergency button under the counter.

“Outside is good.”

It was only two miles from the school and Big Scary Woods, but I felt safer at the convenience store, even if sleeping outside, because I could theoretically get inside somewhere faster, and there were people around in case something went sideways. Plus, what if that nice man had left as a ruse, and would come back later to find me alone?

I scouted the parking lot and walked around the building. In the alley out back, there was a space between the back of the building and a small room off to the side that led to a washer and dryer. Beside the room was a pile of odds and ends from the store such as old racks, buckets of paint, and empty plastic containers of milk. Across the alley were a few houses with porch lights on. A dumpster sat at the far end of the alley. The search was over. I had found the perfect place to sleep.

I set up camp, locked up my bike, and then used the bathroom inside the store to brush my teeth and get ready for bed.

As I walked back outside, the motion detector light went on next to my tent. A few feet from me were stairs that went up to a second-floor apartment. The door opened and a young man came out to smoke a cigarette. A few minutes later his mother came out behind him. They stared at me without saying a word. I smiled and waved.

“Sorry for the inconvenience,” I said. “I’ll be gone early in the morning.”

The mother smiled and the son continued staring. Rings of smoke drifted down and encircled my tent. Not that different from the smoke of a campfire, I thought.

I lay down on my sleeping pad, exhausted from the day’s events. I quickly fell asleep. What seemed like seconds later, a car came through the alley only feet away from my tent. The noise triggered the dogs across the street to bark and, in turn, the owner came out to yell at them to shut up.

I shifted position, closed my eyes, and drifted off again. As if in a dream, the pervasive odor of cigarette smoke enveloped my tent again, and the escalating voices of mother and son arguing, the sensor lights were triggered by someone walking near my tent. An elongated shadow moved across my rain fly and disappeared into the distance.

As I lay there semi-conscious, I imagined a bear trying to get into the dumpster just feet away. I became hypervigilant to any sounds coming from that direction. It didn’t help that the dogs slept outside and continued to bark at any disturbance throughout the night. I looked at my clock. It was only midnight. I stared up at the ceiling of my tent wide awake.

I must have fallen asleep at some point during the night because I woke up with the sun on my tent. I gathered my clothes and toiletries and shuffled into the store with my unruly hair and my pajamas still on. The owner was back on duty. He looked at me as if a Sasquatch had just wandered in. I laid my dollar on the counter and filled up my mug with strong, bitter coffee, then headed straight to the restroom as if I lived there.

I broke down camp, loaded up my bike, thanked the owner again for his generosity, and rode out of town. I was happy that I had survived my first night of wild camping. The first night is always the hardest.

Denise LaFountaine lives in Seattle and is a teacher in the College and Continuing Pathways department at Renton Technical College. She is known to take a quarter or three off each year to travel the world. In her free time, she likes to read, write, swim, dance, tell stories, and have dinner with friends and family.

Speaking a Different Language

by Scott Christiansen

With my boyhood dream of riding across the country diminishing with each passing year, I finally started training for a ride in my early 50s. I got permission for the trip from my patient, noncyclist wife and I invited my 21-year-old, insanely fit son Beniah along (fully intending to draft him for the entire ride). We mapped out a route that started in Bay Center, Washington, and ended in Camden, Maine, a day’s ride from my home in western Maine.

I was intent on doing the ride in a month, simply because that was all the vacation time I had saved up. We’d be keeping up an average pace of over 100 miles a day — every day — so the ride would be a real personal challenge. More than that, though, the ride also offered a professional opportunity: I could write my next book about the ride, or a whole series of articles, or use some part of it in screenplays. For a born storyteller, I knew the opportunities would be significant.

But the stories didn’t come. Sure, things happened. Our first day, from Bay Center to Randle — 132 miles — was done on May 1, 2016, on the same day an all-time high-temperature record for the area was set. 132 miles in temperatures hovering around 90°F and a fair elevation gain on our way to the Cascades makes for a good story. But when I called my wife that night for my safe-arrival report and she asked me how it went, I struggled to respond. The story of the day didn’t come out, and I instead found myself telling her that we’d dipped our rear tires in the Pacific by dawn light and then started riding. I faltered, hesitated, then told her about what didn’t happen — we didn’t have any accidents or incidents, we weren’t too sore or chafed, we didn’t get dehydrated.

Hanging up, I was surprised I didn’t tell her my story, and I was equally surprised the next day and all of the next week when I also didn’t tell her my stories. I didn’t tell her about crossing the Cascades at White Pass or the joyous downhill run into Yakima, arriving a bit after sunset. Or about our route through the eastern Washington desert (in a continuing heatwave) and our relief at finding water at a small rest area next to the Columbia River. I didn’t tell her we reluctantly decided to ride the edge of Highway 90, then, after about 10 miles, I realized I loved riding the edge of an engineered highway with a breakdown lane and rumble strip separating me from traffic that might as well have been a world away. I did, in fits and starts, try to tell my wife some of those stories or just describe the many working pieces of our day. But to my consternation, nothing came out.

It wasn’t just my wife. To make our miles every day, we couldn’t take the weight and time required to camp so we checked into hotels each night. Usually, the hotel staff would express some measure of curiosity about our ride. Often, they’d ask where we’d come from that day, and when we told them, their eyes invariably bugged out. They’d ask where our ride would end, and their eyes would bug out again. Then they’d ask the questions I’d learned to dread, the question whose answer escaped me. “Riding across the nation — what’s that like?”

I faltered, hesitated, then told her about what didn’t happen — we didn’t have any accidents or incidents, we weren’t too sore or chafed, we didn’t get dehydrated.

I could paint word pictures of small snippets of the trip — like hypothermia while crossing the Continental Divide in a very wet snowstorm outside Lincoln, Montana, and flagging down a savior in a pickup truck. Or dispiriting headwinds across Montana and North Dakota. Or how we dreaded our arrival in Fargo, knowing that it would mean the end of legal riding on the edge of the highway. I could tell them we slept through the whole ferry ride as we crossed Lake Michigan, or about the miracle of not getting rained on once the whole trip. Or the blissful peacefulness of a bike trail in New York once we finally got off the road, or the joy of riding into Vermont and being on roads I began to recognize by sight. I mentioned how we grit our teeth and forced ourselves to make our miles. Every day. No matter what. The way my heart soared when I saw my beautiful wife by the side of the road just inside the Maine border, smiling and filming us. Or the relief at leaving our packs at home on our final day into Camden and the joy of dipping our front tires into the Atlantic on the dock, surrounded by friends. And I could describe, or try to, the utter strangeness of driving home from Camden after a month on a bike. But after an anecdote or two, I always stammered off.

On that strange drive home, I finally realized why I couldn’t tell my stories. In moving from the bike to the car, I had left a world in which everything had to be planned and carefully balanced and had re-entered a world which all I had to do was press an accelerator. I had left behind a world in which the quality of the entire day was determined by the direction and speed of the wind, the temperature and presence of cloud cover, the elevation to be attempted, and the width and quality of the apron at the edge of the road. I had re-entered a world that was defined by things that had nothing to do with the natural elements, where grit and sweat and determination did not define the quality or achievement of the day. When I started our trip across the country, I had entered a different world that operated on strikingly different terms than I was used to, and to describe it required using a different language — a language that people who didn’t share common experiences simply couldn’t understand.

For a few days after my trip, I continued to try to tell people what my trip was really like — how amazing it was, how transformational it was, how we struggled against things that were unseen and unconsidered by most people. Then I stopped. Watching them lose interest in, then politely endure, a description of factors and forces outside their frame of reference was simply too painful. I wanted to tell them about a crowning achievement of my life, but I quickly came to the point in which, in response to a query, I would simply smile, tell them it was tiring, make a pedaling motion with my hands, and say that I remembered “quite a lot of pedaling.” Most people didn’t have a follow-up question, and no wonder — there was no common experience on which to build communication.

I recently challenged my two grandsons, now five and seven, to a tri-century ride over a long weekend in 10 or 11 years. I’ll be 70, and if I can make it, it will very likely be my last big ride. But I desperately want to stay in shape and make that ride. I want to have that experience with my grandsons, to be able to smile and wink at them in my old age and know that we share experiences and accomplishments that few others understand. I want them to speak my language.

Scott Christiansen is a writer, author, and biorefining consultant. He lives in the foothills of western Maine with his wife, his dog, and his humble but steadfastly reliable Specialized Sequoia.

Not Every Part is the Fun Part

by Emma H. Rehm

The road to Piedra Blanca was deeply sandy, and we hardly stopped because it’s so hard to restart on sand. My companions were my partner, Q, and our beloved friend Sara — all of us mountain bikers and tenderhearted dirtbags from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In those long stretches of loose sand, each of us took turns leading to pack down a track for the others to ride in. It’s a very particular kind of moving meditation, pedaling slowly and gently but consistently, never stopping. When it goes well, and you find the rhythm and pace, you can lock into a beautiful blissed-out state. But when you’re overheated or anxious or cranky or agitated, it’s so hard to find peace, which means it’s harder to stay in the track, and any time you waver off the line, your wheel sinks in the sand and you have to start all over again, making you crankier and more agitated. So you learn: find peace; stay on the line; don’t hurry, but don’t stop.

The sand eased up in the morning, but my brain didn’t switch back over to “stopping is okay” mode as the road became deeply washboarded for miles and miles. The washboards wore on my wrists and the vibration made me nauseous. Q and Sara had no trouble riding them and cruised ahead of me. Sand is arduous, washboards are taxing, and the combination is a special kind of grueling, but, “At least it cushions the blow,” said Sara.

I pushed to keep up, getting more queasy and dizzy and headachey by the mile. They stopped and I eventually caught up, looking fairly awful. Q asked if I was doing okay, and this tiny gesture of kindness opened the door for three tears to slide down my cheek.

“No!” I said. “I think I’m going to throw up!”

All I had to do was stop, let some air out of my tires, and ride as slowly as I’ve ever ridden in my entire life. I didn’t throw up.

On a sign in the middle of nowhere that maybe once had listed a town or ranch name but was now completely covered with stickers on both sides, one stood out: the black one that read, “F!%# Cancer.” Carol will love this!, I thought. Just before I left Pittsburgh for this trip, she and I had taken a double middle-finger selfie, because cancer is the worst.

As soon as we got to Mulegé and back into cell service, I texted the photo to her. Ten minutes later, I received an email saying she had died earlier that day.

She’d promised me she would do her best to still be alive when I got back, and I know she did her very best.

On a sign in the middle of nowhere that maybe once had listed a town or ranch name but was now completely covered with stickers on both sides, one stood out: the black one that read, “F!%# Cancer.”

I had crazy violent nightmares the night before we left Constitución, and in the morning I was exhausted and emotionally fragile. The first thing to do was ride through the dump, a literal burning trash fire. I was spent and still oblivious to the impact of grief on my body. Some lessons don’t come quickly.

I can ride rocks for days, but I can’t handle a flat road, or a straight road, or washboards. Individually, they are all so hard for me. Together, they are my kryptonite. As we exited the dump, we turned onto a straight, flat, washboard road of misery for miles. I stopped to stretch, and when I folded over, more tears fell out of my face. I rage-sobbed in the middle of the road.

We finally turned onto a different road, a wiggly, chunky, wonderful one, probably only a quarter-mile long, before turning onto another straight road. This time, though, some unknown switch tripped in my brain and my body. I felt myself riding stronger, feeling less pathetic. Not every part is the fun part, but that’s okay — I know how to suffer, I know how to struggle.

Q caught up with me and said, “Remember that time you were feeling all punked out and having a hard time keeping up, and then we turned onto a different road and you screamed, ‘I AM A MOTHERF!%#@R!’ and took off and left us in the dust?”

Is that what happened? I guess it could be.

I knew at some point there would have to be a curve in the road — a bend, a hook, a gentle rise, anything — and I was going to find it. I was going to ride straight on through, no stops until I got there, however far away it was.