A Curtain Parts

This article first appeared in the September/October 2023 issue of Adventure Cyclist magazine.

The spring of 1968 in Czechoslovakia was no ordinary time. And as it turned out, Jaroslav Jung was no ordinary 21-year-old. Revolution was in the air. The turbulence that spread throughout cities all over the world blew through the Iron Curtain that year and took root in Prague. Out of the ferment of that fateful spring, Jaroslav planted a seed of hope in the form of an ambitious, moonstruck plan for an expedition, a bicycle tour to showcase to the world the bright future toward which his country was headed.

Part One

Fueled by boundless youthful enthusiasm, resourcefulness, a love of the outdoors, and a yearning for long-denied freedom, Jaroslav, along with two friends, hatched a plan to travel by bicycle from Prague to Amsterdam, then fly to New York and bicycle from New York across the U.S. and down to Mexico City in time for the 1968 Summer Olympics. The trip was to be a cultural exchange, showing the world the new Czechoslovakia as it embraced “Socialism with a Human Face.”

The Czechoslovakia of Jaroslav’s youth was a country under occupation, as it had been for almost two decades before his birth in 1946. First the Nazis and then the Soviet Communists squelched any vestiges of democratic governance, transforming this peaceful, beautiful country into an impoverished land where everyone was equally poor, living paycheck to paycheck — everyone, that is, except for top officials of the Communist Party. There was no freedom of press or assembly. Anyone who expressed criticism of the government was considered an enemy of the state and arrested. Secret police were a pervasive albeit invisible presence, creating an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. Badly run government agencies caused shortages of food, clothing, and other consumer goods, and what was available was too expensive to afford. There were long lines for nearly all basic needs, including medical care. Travel to the West was banned. The borders were sealed, surrounded by sand strips, land mines, and barbed wire fences, with round-the-clock surveillance by military guards and sharpshooters. Growing up in Czechoslovakia of the 1950s and 1960s, the very idea of going to America was nearly as much a fantasy as going to Mars.

Coming of age in such a repressive, constraining environment, Jaroslav turned to where he felt most free — the great outdoors. He learned to ride a bicycle at the age of three, guided by his father, a two-time gold medal cycling champion in the University Olympics and a silver medalist in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.

For Jaroslav’s family, cycling was more than their transportation; it was their way of life. It was extremely rare to own a motor vehicle in Czechoslovakia at the time, so his family would often pedal 50 miles a day from Prague into the countryside.

“Often, with my parents or alone, I would pedal through rural Moravia, Slovakia, and Sumava for weeks at a time,” Jaroslav recalled. “I remember, once, after pedaling all day with my parents, we stopped to eat dinner and I hungrily ate our only can of sardines, not realizing it was dinner for three of us!”

In his teens, Jaroslav developed another passion, one that paired well with his love of the outdoors: photography. With a camera lent to him by a friend, he began taking photographs of his mountain climbing expeditions. On a whim, he sent some of these photos to Nikon’s Zurich headquarters, and, to his delight and amazement, they were accepted for use in Nikon’s European advertising campaigns. In exchange, Nikon presented him with three cameras and three lenses. Just like that, his hobby became a new profession.

Massive student protests in Czechoslovakia began in 1967, leading to widespread repressive crackdowns and arrests. As the main photographer for the magazine Student, the only press that dared cover the protests, Jaroslav was a frontline observer. What started as a tentative tremor gradually became a groundswell movement for social and political reform. By March 4, 1968, for the first time in Czech history, there was a complete abolition of censorship. A new first secretary of the Communist Party, Alexander Dubcek, was openly promoting new freedoms of media and travel to the West. The excitement was palpable throughout the country. Jaroslav was like a coiled spring trapped in a tight box, desperate for freedom. But with no money or resources, travel to the West remained evasive. He needed a plan.

Drawing from his two greatest passions, bicycling and photography, as well as an exuberant pride in the new Czechoslovakia, Jerry devised a plan. He would cycle across Europe and the U.S. to Mexico City in time for the 1968 Olympics and promote the new “Socialism with a Human Face” along the way. “I was excited thinking of the photos I would be inspired to take, all the amazing adventures I would have, the interesting stories I could share, and the ability to meet my aunt and uncles who had sent care packages through the hard times,” Jaroslav recalled. “I knew it would not be easy to pedal up to 300 kilometers (187 miles) in a day, with challenging terrain through mountains, desert, and unpredictable weather. But once the idea got into my head, I realized that I had to do it.”

It was March 1968. The Olympics were to start in October, a mere seven months away. He enlisted two friends, the very athletic Ilja, and Milos, a 42-year-old bicycle mechanic, to accompany him. They would visit universities and youth organizations to establish an exchange of ideas with American and other European students. Using his photographic and journalistic skills, Jaroslav would document the trip in detail. His Czech press card (and some helpful connections along the way) would grant him access to newsroom resources like darkrooms throughout his trip, meet prominent people, and attend cultural events, museums, and landmarks. He would give interviews and send progress reports to the press and his sponsors. And finally, after returning to Prague, as the grand finale, he would have a photo exhibition and write a book.

Before this plan could get off the ground, though, Czech government approval would be needed, as their official support was essential for Jaroslav and his team to be considered legitimate ambassadors of Czechoslovakia. Given how Czech bureaucracy was known to be notoriously slow and obstructive, it was astounding how quickly, even enthusiastically, they provided all the necessary documents.

Next, they needed sponsors. Their youthful enthusiasm and handsome athleticism made them irresistible as the fresh faces of the new Czechoslovakia. One by one, sponsors jumped at the chance to help. Pan American Airlines agreed to provide flight tickets to New York and from Mexico City to Prague, as well as T-shirts, travel bags, and cases with their Pan Am logo. Nikon supplied cameras and lenses. Kodak and Ilford sent them film. Various Czech companies supplied three custom road-racing bicycles, outfits, parkas, windbreakers, canned food, walkie-talkies, a typewriter, and replacement tires, parts, and tools to be cached throughout Europe and America for necessary repairs. In the U.S., Czech expats and relatives who had emigrated, contacts through school deans in Prague, even a network of Czech bartenders who had emigrated — they all wanted to be a part of this historic odyssey.

Amid dense crowds and much fanfare, with TV crews and journalists all jockeying for a glimpse of these young explorers, on May 27, 1968, the trio departed. In a gesture of recognition that they were cycling from the Old World to the New, they chose to begin their expedition from Prague’s Old Town Square (Staromestské namestí) in front of the world’s oldest working astronomical clock, the Orloj, built in 1410. As they rode off with their panniers full of gear, an acquaintance they passed yelled out, “Guys, where are you going?” Jaroslav yelled back, “We’re going to America!” triggering incredulous laughter.

As they rode across the iconic Charles Bridge, which spans the Vltava River in Prague and was originally constructed in 1357, Jaroslav suggested they stop at the statue of the first Russian tank that arrived in 1945 at the end of World War II. That first tank was the harbinger of the end of Nazi occupation and the beginning of Soviet occupation. Jaroslav remembers saying, half-jokingly, “Let’s take two minutes of silence here, because who knows what Czechoslovakia will be like after we return from the Olympics.”

Part Two

The emotional high from all the attention provided a strong tailwind as they cycled out of Prague. They felt like stars in some epic movie, invincible heroes on a noble quest. As they approached the Czechoslovakian border with West Germany, the Iron Curtain, anxiety clouded their sunny exuberance. All the recent reforms and newfound freedoms seemed so fragile, so tenuous. The sight of the border guards triggered a fear that all their grand plans could be washed away in an instant, like delicate young seedlings in a sudden thunderstorm. For the entirety of their young lives, those uniforms had been the straitjackets to their freedom. After a nerve-racking hour of careful examination of their documents and bags, the guards’ demeanors softened and they wished the three well on their journey to the New World.

Relieved to have passed the first big hurdle, Jaroslav found cycling through Germany pleasantly familiar yet excitingly new; the countryside reminded him of the many pleasant weeks he’d spent as a child cycling with his parents touring rural Czechoslovakia. Here in Germany, though, everything seemed brighter, happier, and cleaner. After a moment of worry when German police checked their documents, they felt free, truly free in the free world!

They were flooded with invitations: to join local mountain climbing club expeditions, to give radio interviews, to meet with local university student organizations, even to meet the president of the European division of Nikon, where once again they were given yet more camera equipment. It was a comforting reassurance that if they were taking a leap into the great unknown, they wouldn’t be left to fend for themselves.

The first hint that the free world might not be free of the turbulence they had left behind came as they were visiting the Zurich plant for the newspaper Tages-Anzeiger. They stood next to a row of teleprinters, chatting with the editor, as the presses rolled out the headline news of Robert Kennedy’s assassination in California, one of their planned stops en route to Mexico City.

Of all their stops in Europe, Paris was for Jaroslav the most highly anticipated. When they arrived in the City of Light, though, the streets were choked with massive student demonstrations and the largest general strike in France’s history, reminiscent of those they’d witnessed in Prague but even more widespread and paralyzing. The realization dawned on them that the Prague Spring might have been part of something much larger, spanning borders.

With all public transportation frozen by the strike, their bikes gave them independence and ease of movement within the chaotic city. They pedaled right to the George V Hotel on the Champs-Élysées, an oasis of Old World elegance and calm amid the turmoil in the streets. There they met with Rudolph Slavik, a Czech expat of some renown, who held court as bartender par excellence. He handed them special passports that he portentously instructed them to show to bartenders along their expedition, with individual letters from himself that they were to deliver. He assured them that they would be received as honored guests in these bartenders’ homes. They accepted this unquestioningly, but to this day, Jaroslav wondered if they were unwitting messengers, passing coded messages between spies.

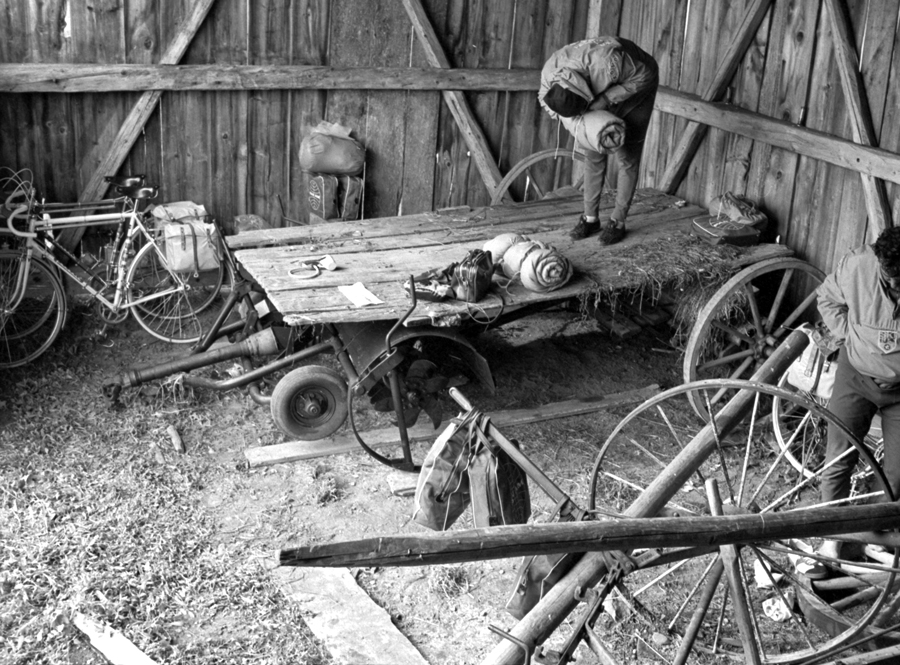

To avoid the chaos of the city, they slept in a barn outside of Paris the night before their departure for Brussels the next day, an epic dash of 199 miles that would take them 12 hours.

Civil unrest had spread to Brussels as well. They had instructions from FAMU, a film school in Prague that Jaroslav had attended, to deliver letters to deans and presidents of universities along their route in Europe and the U.S., with the hope of opening new markets abroad for FAMU. When they arrived at the University of Brussels to meet with administration officials, they were once again immersed in massive violent student protests that engulfed the campus. The scene was scary. Numerous police officers were taken away in ambulances. Five very large students attacked Jaroslav and seized his camera, tore out the film, and refused to give it back until Ilja explained in French that they were themselves students and not government agents.

In their minds, all the miles they had traveled from Prague were just the warm-up for the main act: America. With their flight to New York from Amsterdam imminent, they set out on the final leg of the European phase of their trip, arriving early enough to enjoy their first glimpse ever of an ocean, the Atlantic, that they were about to cross on their very first flight on an airplane.

New York came as a shock. Their only real experience of a big city was Prague, where the streets were empty and the summers mild. In Prague, life happened behind closed doors, and in the streets there was a general atmosphere of somber tension and restraint. Not so here in New York, where the heat was stifling, the streets choked with traffic, fumes, and people yelled amid a deafening cacophony of sirens and honking horns. It was unlike anything the three had ever seen. Even the chaos of Paris didn’t compare. For Ilja and Jaroslav, it was dazzling, but for the 42-year-old Milos, it was overwhelming. Almost twice the age of his cycling mates, Milos had health issues that turned out to be more serious than he had acknowledged. Within days of their arrival in New York, it became clear that Milos couldn’t continue the expedition and, thanks to a quickly arranged complimentary Pan Am ticket back to Prague, he went home to recover.

The remaining duo found refuge from the roiling city in the apartment of a childhood friend who had escaped Czechoslovakia in 1962, although the heat was so intense that Jaroslav slept in the cool iron bathtub. They spent their days in New York adjusting and preparing. A visit to Pan Am’s headquarters on Park Avenue provided another reassurance of corporate support, where they delightedly accepted a $400 check for publicity expenses, which would feed them for two months.

They had official visits to the United Nations Czech delegation, to Nikon headquarters, and Time Life magazine, where they were interviewed, as well as museums and tourist sites they had dreamed of seeing for years. Arriving at Columbia University, they were greeted with student demonstrations against the Vietnam War and general chaos, a scene reminiscent of those in Paris and Brussels. In what almost seemed like a comic refrain, once again a protester grabbed Jaroslav’s camera and tore the film out.

As they left New York heading to Washington, DC, and points west, Ilja and Jaroslav had settled into a daily rhythm. They would cycle much of the day, then each night, in preparation for the following day, Ilja would plan their route and type up press stories to mail in the morning. Jaroslav would mark the day’s film rolls by location, place them in protective bags and seek out local newspaper offices where, thanks to his press card, he was allowed access to dark rooms to develop the negatives and make prints to mail back to Czechoslovakia in the morning along with Ilja’s text copy.

Heading away from the East Coast, the journey to Chicago felt like a long, lonely slog. The landscape became less interesting; they had no connections. They were always hungry, excited at the sight of a McDonald’s where they could get a hamburger for 18 cents. Chicago felt like a sight for sore eyes, but without any connections there either, they felt disinclined to linger. Here a woman overheard them speaking Czech and gave them a $5 bill. This gesture of solidarity couldn’t have come at a better time, lifting their low spirits.

The section from Chicago to Omaha was brutal. The daily temperatures were over 100°F, with unending, flat, empty space. Dusty and sweaty, doubts crept over them. Arriving in Omaha to a warm welcome from Jaroslav’s godfather, namesake, and great uncle, Jaroslav, felt like divine salvation. Having left Czechoslovakia before World War I, elder Jaroslav had settled in Omaha and, over the years, sent to younger Jaroslav’s family care packages of goods such as coffee, salami, chocolate, and jeans, not usually available in Czechoslovakia. Meeting his great nephew for the first time, the elder Jaroslav spoiled them with more homey comforts than they ever had back at their actual home in Prague. It was hard to pedal away from this deep familial love.

When they arrived in Denver, they discovered that whatever his ulterior motives may have been, the well-connected Rudolf Slavik was as good as his word. A bartender on Slavik’s network welcomed them into his luxurious home with stables and horses. Through their host, they visited the U.S. Olympic Village outside Boulder, where they saw athletes training. As if crossing the Rockies by bike wasn’t enough of a challenge, for a change of pace, they joined the Colorado Mountain Club on a climb in freezing rain where they spent a miserable, snowy night in a cave. After that, getting back on their bikes felt like a relief.

Fewer connections out west meant fewer diplomatic obligations, and they were able to be tourists. Yellowstone National Park felt like exploring another planet. After witnessing so much social unrest and turbulence, seeing the natural turbulence of erupting geysers was awe inspiring. They turned their diplomatic skills toward the natural wildlife, at times somewhat misguidedly. Having never seen a moose or a bear before, Jaroslav couldn’t stop photographing these creatures who seemed very curious about people. As he was engrossed in photographing a bear, a passing tourist cried out that another bear was approaching him; Jaroslav yanked his leg just as he heard its jaws snap!

Las Vegas was a full Technicolor assault on the eyes, its unrestrained vice and sinfulness on full display. Jaroslav, captivated by the casinos, photographed them until security escorted him away. He later discovered that men gambling without their spouses’ knowledge preferred to keep their presence there away from a camera lens.

From there, they rode on to Yosemite, for which neither the High Tatras in Slovakia nor the Rockies they’d so recently traversed could prepare them. The ride into the valley was the most challenging day of their entire trip, with unrelenting climbs and heat. Their arrival felt like being delivered into the Promised Land, a sacred place of unimaginable beauty and a gateway into magical California. They were so entranced by the place that they gave their bikes a rest to climb El Capitan to see the valley from up high and take photos of the climb for Nikon.

It was more than just astounding natural beauty that California offered the two explorers. Their extensive and eclectic network of acquaintances, relatives, and friends led them to encounters that, back when Jaroslav was first planning the expedition, he never would have imagined possible.

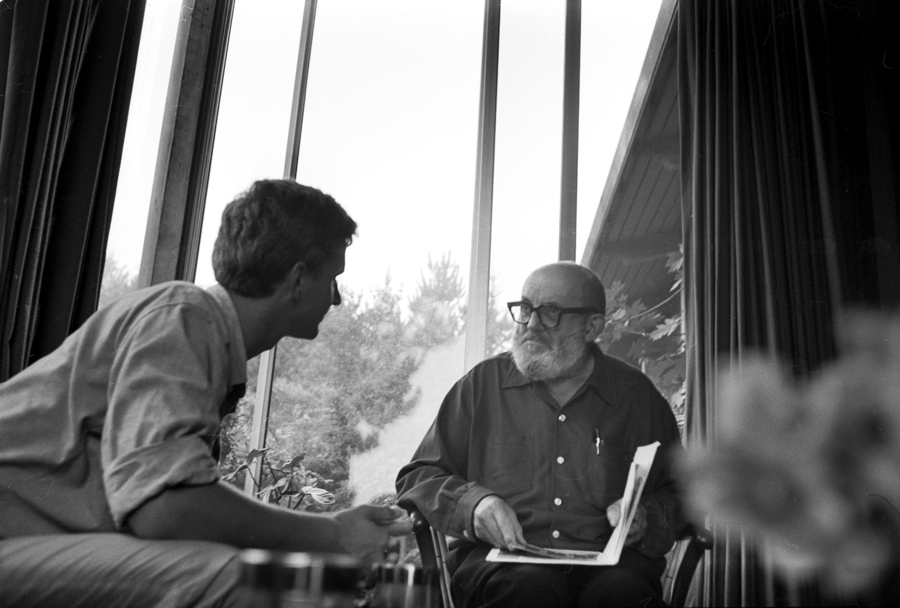

In San Francisco, Jaroslav found a photo lab owned by a Czech expat who let him process his photos. After looking at Jaroslav’s work, the owner set up a meeting for him with the renowned photographer Ansel Adams at his home in Carmel-by-the-Sea. The two had a delightful lunch together during which Adams looked over Jaroslav’s work and gave him sincere encouragement.

After cycling from Carmel-by-the-Sea to Los Angeles down the Pacific coast on the famed Highway 1, through the ancient redwood groves of Big Sur, Jaroslav was contacted through the Czech embassy by his aunt Natasha, whom he hadn’t seen since his infancy and who had tracked him down after reading a newspaper article about his bicycle expedition. Natasha had left Prague at the end of World War II and was living with her Mexican film producer husband Jacques Gelman in Mexico City. Eager to see her nephew, Natasha arranged a reunion at the home of their old friend, the film star Edward G. Robinson.

For all the support and cultural agility, the trip wasn’t without a few flubs, especially with the exhaustion of pedaling and meeting so many celebrities. At the home of Olympic gold medalist Peggy Fleming for lunch, her mother served green gelatin, Jaroslav’s first time seeing it. When asked if he wanted some, his English failed him. “Fak’ no” is a reasonable response to such an offer in Czech, fak being the slang for fakt, meaning “fact.” But for some reason, the whole table went very silent after that.

The Los Angeles Times interviewed Jaroslav and Ilja about their expedition, but when they emerged from the newspaper offices to retrieve their bikes, they found that Ilja’s bike had been stolen. The reporter writing the article integrated this new twist into the story and focused on the theft that halted the journey. The article was printed the next day, filling page three. The newspaper staffers were determined to not let this end the story, however. They contacted the Los Angeles Wheelman Club and Huffman Manufacturing Company, which would eventually become the ubiquitous Huffy Corporation. Within a matter of days, Ilja was presented with the gift of a brand-new high-end bike; their mission was revived!

With a new bike and a lifetime of support, it was time to turn south for the final leg toward Mexico City. The evening before their departure, Ilja gave a press interview by phone. Afterward, as they were preparing for the next morning’s early departure, they listened to a small television in the guest room where they were staying. The voice of news anchor Walter Cronkite announced a special report that caught their attention: Czechoslovakia was under siege. Russian tanks were rolling through the streets of Prague and into all the main squares, including the one where their expedition had begun two and a half months earlier. Thousands of people were in the streets, encircling the tanks, shouting at them in anger. Tanks were firing at the National Museum and surrounding buildings. Reports said thousands of troops were landing at the airport.

“Russia wanted to crush our brief period of liberalization, to end Prague Spring, our hopes of new democratic freedoms, [our] reforms to the communist system,” Jaroslav remembers now. “Socialism with a human face” had been the motivating theme of their expedition. Jaroslav and Ilja had given dozens of interviews in all the countries they’d passed through, highlighting and celebrating human freedom and condemning past communist restrictions to those freedoms. With a chill, they realized that under the return of Soviet occupation, they would be severely punished or imprisoned if they returned. At that moment, in front of the television set, they knew that not only was their expedition over, but their families, their friends, their homes, and their homeland were in danger. The life that they had known up to that moment was gone. They could never go home.

Part Three

There was hardly any time to process what happened that fateful day or to mourn the end of their dream of a triumphant arrival in Mexico City. Very quickly, Jaroslav realized that his parents were in imminent danger and that his mission had abruptly changed. He needed to get them out of Czechoslovakia and fast!

He remembered that his parents would already be out of the country, as they had just gone on their own first trip to the West, to Paris, though that day they were scheduled to take a train back to Prague. Thinking it was possible, in that pre-internet era, that perhaps they hadn’t heard about the invasion, maybe there was still time for them to get off the train before it crossed the Iron Curtain — if only he could tip them off in time. In desperation, he sent them a telegram to the Nuremberg train station, just before the Czech border, praying that they would get it in time. On the evening of August 21, he called their apartment in Prague, praying they wouldn’t answer. When his father picked up, Jaroslav’s heart sank. They could be trapped in Prague for decades. They had indeed gotten the telegram, his father said later, but he crumpled it up and stayed on the train because “his country needed him.” Noble, for sure, but this complicated the picture. As soon as the Russians realized that Jaroslav wasn’t returning home, they would clamp down on his parents, spying on them and restricting their mobility, using them as leverage to pressure Jaroslav to return.

Jaroslav received a suspicious letter from Czech president Ludvik Svoboda, delivered through the Czech embassy, offering him amnesty if he returned home by September 1969. Otherwise, it said, he would be arrested and punished. Knowing the offer could not be trusted, Jaroslav got to work. It took him about a year, putting in long hours at three photography jobs, to earn enough to open his own photo studio and buy his parents plane tickets to the U.S. In secretive coded letters to them, he sent instructions on where to pick up visas and plane tickets and when to leave. Not knowing whether his messages had gotten through or been understood, or if they ever boarded their flight, he waited in a state of almost unbearable tension at the airport in Los Angeles on the day of their flight, September 4, 1969.

After a long delay, they finally appeared, carrying only two suitcases. They traveled light to create the appearance of the intention of returning home. But the transition to life in Los Angeles was rough. Living together in a tiny Hollywood apartment, his mother, who spoke no English, felt isolated and despondent. After weeks of hearing her crying, Jaroslav was no longer sure he’d done the right thing bringing them to the U.S. One day, while driving with his father, he suggested that maybe they should return home after all. “I can’t go back,” his father said, “because I’m a spy.” Many years before, Communist Party officials had approached him with an ultimatum: either spy for them and they would let Jaroslav attend college or, if he refused, Jaroslav would be sent to forced labor in the dangerous, toxic Jachymov uranium mines and never have a future worth living. Jaroslav’s mother had never known about this secret deal his father had made. Finally, during a bout of sobs lamenting her parents and country, she finally learned the truth and that they would not, could not, go home.

“Socialism with human face” was finished after the invasion. The magazine Student that Jaroslav had shot photographs for was immediately closed, the editors badly beaten. “No more freedom of press, speech, no more freedom of travel,” Jaroslav recently recalled.

The Velvet Revolution, the peaceful transfer of power that ended Soviet rule, swept over Czechoslovakia in 1989, as it had over all of Eastern Europe. The Berlin Wall fell.

By 1990, Jaroslav felt it was time to revisit his homeland for the first time in more than 20 years; he was nervous and wary. He remembered all too clearly those heady euphoric times of the Prague Spring and the launch of his bicycle expedition, the trip that changed his life, and how all that hope and promise had dissolved like the end of a pleasant dream upon waking. But nothing could efface his love of cycling.

Back in Czechoslovakia, border police checked and rechecked his U.S. passport suspiciously, conferring in hushed voices for what seemed like an hour, taking Jaroslav right back to all the fear and tension of a childhood within a police state.

He was allowed to enter the country, but only a few days later, while driving on a quiet country road, two armed soldiers on horseback yelled, chasing him at full speed until he stopped. Another thorough, nerve-racking examination of his papers followed, leaving him in a state of anxiety, even after he was waved on. For all the upheaval and changes in his homeland, he had become a stranger there. That mission back in 1968 of showing the world the great promise of his homeland’s future had, after much wrenching trauma, brought him to a new homeland. He was now an American.